Han Han Capsule Reviews

Duckweed (2017) — July 3, 2017

Race car driver, essayist, and film director Han Han had one of 2017’s biggest hits with Duckweed, a time travel comic drama about a son learning to respect his father. An update of Peter Chan’s 1993 classic He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Father (Chan and his film are specifically thanked in the credits, along with the directors of Back to the Future, The Terminator, and Somewhere in Time), Deng Chao plays an angry young racer who publicly spits venom at his aged father (Eddie Peng) during a victory speech. When the two are in a car accident on the way home, Deng falls into a coma, where he is transported (somehow, the film, thankfully, doesn’t care to explain how) back to 1998, where he befriends his father as a young man. Peng is the morally upright leader of a small gang, with one dim buddy, a loving girlfriend (Zhao Liying), and real-life future internet kajillionaire Pony Ma (Chan’s film similarly feature a future tycoon, with a character based on Li Ka-shing). Deng joins the gang and helps them try to navigate conflicts with a local gang leader who wants to criminalize the karaoke bar Peng runs (Peng doesn’t want the girls who work there to prostitute themselves) and ultimately a sleepy-eyed villain/real estate developer. At the same time he gets to know Zhao, whom he never met (his mother died shortly after he was born).

Much of the comedy is based in Peng’s inability to anticipate the future: he’s heavily invested in beepers and VHS tapes, linking his outdated ideas of technology to a moral code rapidly becoming obsolete in an increasingly capitalist China. Where in Chan’s film the younger man learned that his father was a community leader holding together a House of 72 Tenants-like variety of refugees and the working poor, Deng’s reference point for his father’s life is something like the Young and Dangerous series, with Peng the stylish hero of a gang of good guys just trying to get by in an amoral world. That alone says something about our debased world, but Han Han doesn’t push it too far. Instead the films skims along neatly through deft action scenes (the vehicle stunts are pretty good, as you’d expect from a former driver) and nifty imagery. With an easy humanity and knack for underplaying comedy, Peng has established himself as one of the great stars of Chinese cinema today.

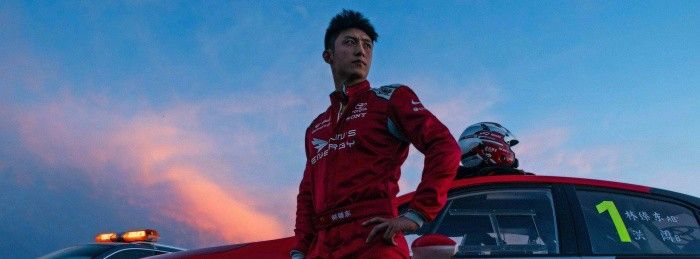

Pegasus (2019) — February 18, 2019

Han Han’s Pegasus, his follow-up to his 2017 surprise hit Duckweed, seems to be a conventional sports movie, but it’s littered with small grace moments that make it one of the better movies about car racing ever made. Han himself was a rally racer (as well as a highly successful essayist, novelist, and musician), and his love of the sport shines in every moment of Pegasus, especially its finely crafted and exciting race scenes. Shen Teng, star of hit comedies Goodbye Mr. Loser and Hello Mr. Billionaire (both directed by Yei Fan and Damo Peng), plays a washed up racer who has had his license suspended for the past five years (he was caught street racing Tokyo Drift-style in a parking garage). His suspension over, he tries to get the gang back together for a comeback at China’s most prestigious, and dangerous, rally race. The film has one basic joke structure: someone says something heartfelt and serious, usually a long monologue, which is then undercut by a new shot or funny line of dialogue, only to have the heart reaffirmed despite the situational absurdity. The result gives the melodrama a patina of cool: the movie is serious but silly but no really it’s serious. This is amiable enough as far as it goes, but the movie really comes alive with the race at the end. Han cuts quickly between cars and racers and on-lookers, deftly incorporating split screens and audio commentary (in both Chinese and English), approaching something like the verve of a live-action Speed Racer.

The end is something wholly unexpected and spectacularly moving, somewhere in-between All About Ah-long and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, an effect only improved by the fact that the screen cuts to black, with several lines of text that whoever subtitled the film for North American release didn’t bother to translate. Not knowing how to read Chinese, I have no idea how the movie actually ended, instead it sits in this magical indeterminate space, one more affecting than a more definite conclusion could ever provide. This is one of the special pleasures of watching these haphazardly released Chinese films: they haven’t been tailored in any way to a North American or art-house audience. As such, there are constantly jokes and references and homages that I completely miss. There are mysterious experiences here that no American film can provide. I get a glimpse of another world, one I can’t possibly comprehend, and it is all the more beguiling for it.