The Shaolin Cinematic Universe

This was originally commissioned by the Vulgar Cinema website in July 2014, and was published in December 2015. Then, after that site disappeared, it was revised and republished at Frame.land in May 2019. Now that site too appears to be defunct, so I'm posting it once again here.

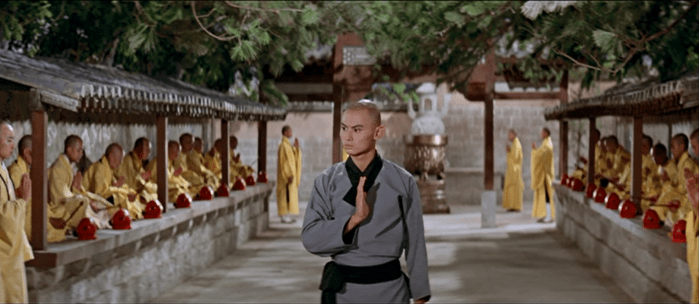

For as many great films as Lau Kar-leung made, and he made a lot of them, the one that he’s best known for today, that still best defines his work, is The 36th Chamber of Shaolin. Made in 1978 and starring his sort-of-adopted brother Gordon Liu, it tells the origin story of the legendary monk San-Te, who enters the Shaolin Temple after his friends and family are murdered by minions of the recently established Qing Dynasty (the Qing general is played by perennial Shaw Brothers villain Lo Lieh). San-Te (known at this point of the story as Liu Yude, he’ll change his name once he achieves monk status) had been active in the local anti-Qing resistance, as the ethnically Manchurian Qing had deposed the ethnically Han Ming Dynasty in the mid-17th Century. San-Te lived some time in the early 18th Century when anti-Qing sentiment was still going strong in Southern China. Fleeing the Manchu soldiers, San-Te takes refuge in the Temple, where he hopes to learn some powerful kung fu and take his revenge.

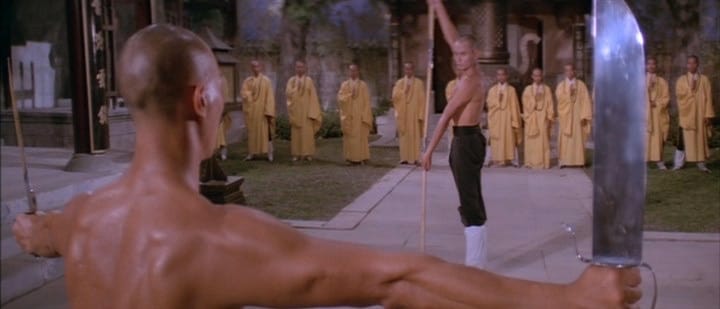

But then Lau gives us the twist: this movie isn’t going to be a simple revenge tale along the lines of the bloody sagas of the other great Shaw Brothers director, Chang Cheh (with whom Lau worked for years as choreographer and action director). Lau patiently leads us through an hour of pedagogy, as San-Te makes his way through the 35 “chambers” of the temple, a series of seemingly innocuous tasks which he must master in order to develop the physical and mental skills necessary to move on to the next stage of his training. Balancing on a log, carrying water, moving his eyes while keeping his head steady, learning to use an immense array of weaponry and even inventing one of his own (the three-sectioned staff, apparently a favored weapon for Lau himself). This middle hour of the film is what has earned 36th Chamber its reputation as a masterpiece, a wholly idiosyncratic devotion to the process and practice of perfecting the martial arts that distinguishes Lau’s work from his more exploitative contemporaries.

But it’s what happens next that interests me: the ways this film connects to the rest of the Shaws Shaolin cycle as well as the kung fu films that followed at other studios in the 1980s and 90s. Taken collectively, these films (and there are a lot of Shaolin films) form an interrelated and at times contradictory mosaic of history and legend. A uniquely cinematic mythology nonetheless grounded in actual events and personages whose transmutation into folk heroes was underway decades before the invention of cinema. These films, focused on the Shaolin Temple as a center for anti-Qing resistance, provide a dizzying metaphorical potential, with the Qing variously standing in for Western imperialists, the Japanese, the Nationalist Kuomintang, the Communists, or even simply the Manchurians themselves, while the Buddhism of the monks allows for examining of the contradictions at the heart of traditional Chinese belief systems, between the imperatives of social justice and withdrawal from worldly concerns.

Upon completion of his training, San-Te is allowed to pick a chamber in which to serve as the new master. He proposes a 36th chamber, one that will entail bringing Shaolin martial arts outside the Temple and into the world, where it can be used to fight for justice. Until this time, the Temple has been wholly isolated, refusing to get involved in the world at large. Outraged (with a wink) at San-Te’s blatant impiety, he is expelled from the Temple for his suggestion, whereupon he proceeds to form his 36th Chamber. Returning to his hometown, he quickly gathers some disciples and begins their training, leading to an attack on the Qing and finally his revenge on Lo Lieh.

Lau makes a point of introducing us to this first generation of Shaolin disciples, for they will go on to appear in several other films. In fact, most of the films in the Shaolin cycle begin with this generation of fighters, the ones that came after San-Te. At some point the Southern Shaolin Temple was destroyed by the Qing (the historical evidence for this, when and if it happened at all, is sketchy, but it has endured as folklore since at least the 19th Century), sending a select few survivors out into the world where they covertly spread their kung fu knowledge while working to undermine the Qing (following the pattern set by San-Te himself). This is the origin story of several strains of Southern martial arts, as well as the organized criminal gangs known as Triads (they are supposedly descendants of Shaolin refugees who gathered at the Red Flower Pavilion to dedicate themselves to anti-Qing subversion sometime after the Temple’s destruction, you can see a version of this legend in the prologue to Johnnie To’s Election).

Among San-Te’s first disciples are Hung Hsi-kuan and Lu Ah-cai. Hung Hsi-kuan is also the hero of Lau’s Executioners from Shaolin, where he escapes the Temple after it is destroyed by the Manchu (because by this time they are outright harboring anti-Qing activists). I may be getting my Chinese names confused, but I believe this man is also Hung Hei-gun, the founder of the Hong Gar fighting style practiced by Wong Fei-hung and eventually passed down to Lau Kar-leung himself. Lu Ah-cai is in some traditions Hung Hei-gun’s student, and then in turn the teacher of Wong Kei-ying, Wong Fei-hung’s father. But in Lau’s Challenge of the Masters, it is Lu (played by Lau Kar-wing, Lau Kar-leung’s brother) who instructs Fei-hung after his father refuses to teach him kung fu (in another version of the story, his father’s refusal to teach him leads Wong to become the student of Beggar So, the Drunken Master). I don’t know who the other disciples (identified as Tung Chien-ching and “Miller Six”) are supposed to be, or if they are meant to represent any famous figures at all.

With the aim of untangling some of these interconnections and highlighting some of the ways these films, made by men with different aims at different times and drawing on similar but different traditions, fit together to form a not-quite-coherent chronicle of recent history that probably says more about Hong Kong over the last half of the 20th Century than it does Qing Dynasty China, I’m going to attempt to put the Shaolin films into a chronological lineage, from San-Te to Gordon Liu and beyond. Note that this only includes the films that I’ve seen. There are many others that could be included just as well.

1. Origin (Early 18th Century):

36th Chamber of Shaolin (Lau, 78) – The beginnings of Shaolin’s involvement with Anti-Qing forces. San-Te goes into the world, recruits the first generation of secular Shaolin disciples including Lu Ah-cai and Hung Hsi-kuan.

2. Destruction (Mid 18th Century):

Shaolin Temple (Chang Cheh, 76) – Deepening involvement as the monks, after much debate, agree to let in an all-star cast of anti-Qing rebels (Ti Lung, David Chiang, Alexander Fu Sheng, the Venoms). They are betrayed from within (by Ma Fu-yi, played by Wang Lung-wei) leading to the destruction of the Temple.

3. Refugees (Late 18th Century-Early 19th Century):

a. Executioners from Shaolin (Lau, 77) – Hung Hsi-kuan (Hong Hei-gun?) escapes from the Temple, vows revenge against the evil monk Pai Mei, who in this version of the story, betrayed the Shaolin to the Qing. He fails, but his son, Wen-ding, after integrating his father’s Tiger Style with his mother’s Crane Technique, manages to defeat the villain (played by Lo Lieh). Lau Kar-leung’s parents where also experts in different styles of kung fu, his father in the Hung Gar style, his mother in Wing Chun.

b. 5 Shaolin Masters (Chang, 74) and Heroes Two (Chang, 74) – Beginning with the burning of the Temple, these two films follow two groups of refugees. In the first, the five heroes head north, where they hone their skills and eventually get their revenge on the traitor Ma Fu-yi. As in 1976’s Shaolin Temple, Ma is played by Wang Lung-wei. David Chiang, Ti Lung and Chi Kuan-chun will also play the same roles in that prequel. The film ends with the refugees gathering at the Red Flower Pavilion to plot their next moves. These are the traditional founders of the Triad gangs. The second film follows the two refugees who head south, Fong Sai-yuk, played by Alexander Fu Sheng (who appears playing a different character in 5 Shaolin Masters, but will return to the Fong role several more times, including in Shaolin Temple) and Hung Hsi-kuan, played by Chen Kuan-tai. Fong is one of the great characters in Shaolin mythology, portrayed many times on film.

c. Fong Sai-yuk Variations:

1. Disciples of the 36th Chamber (Lau, 85) – Follows Fong as a young mischievous schoolboy sent to the temple where he is trained by San-Te himself. Hsiao Ho plays Fong and Gordon Liu reprises the role of San-Te.

2. The Legend of Fong Sai-Yuk Series (Corey Yuen, 93) – Jet Li plays the character in a pair of screwball wire-fu epics. In this version of the story, Fong learns his kung fu from his mother Miu Chui-fa. This is more in line with folk tradition than the Lau and Chang versions of the story, as Miu is traditionally known as the daughter of one of the Five Elders of Shaolin (masters from the time of the destruction of the Temple, but a different five masters than the ones in the Chang Cheh film) and a kung fu master in her own right. The folkloric Fong is known for having killed Tiger Lui in a fight. But in this version, Lui is the ineffectual new Manchu governor and Fong comically marries his daughter. In some versions of the Fong story, he is killed by Pai Mai sometime after the destruction of the Temple.

d. Wing Chun:

Ng Mui was one of the survivors of the destruction of the Temple and is the founder of the Wing Chun martial arts style (named after her disciple, as seen in the 1994 Yuen Woo-ping film Wing Chun, starring Michelle Yeoh). Wing Chun, of course, is the style taught by Ip Man (as seen in six recent films: three by Wilson Yip starring Donnie Yen, two very good ones by Herman Yau, and Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster, starring Tony Leung) and learned by Bruce Lee, as well as Lau Kar-leung’s mother.

4. Second Generation (Mid-19th Century):

a. Ten Tigers of Kwangtung (Chang, 79) – In flashback, a group of anti-Qing fighters gather in Kwangtung (Canton, Guangdong) and continue the fight. Among them are Beggar So, the Drunken Master (played by Philip Kwok, one of Chang Cheh’s 5 Deadly Venoms but best known today for his role as Mad Dog in John Woo’s Hard-Boiled), Wong Kei-ying and Li Jen-chiao, a Shaolin refugee played by Ti Lung. In the framing story, the students of these Ten Tigers continue the fight against the Qing.

b. Iron Monkey (Yuen Woo-ping, 93) – Wong Kei-ying and his young son witness a masked avenger (Donnie Yen) defending the weak against the depredations of the local Manchu government. Both Wongs eventually join in the fight. Like the Wongs, Iron Monkey is both a physician and a martial artist.

c. Challenge of the Masters (Lau, 76) – Wong Kei-ying, now a respectable businessman in Foshan, a city in Guangdong, runs a martial arts school under the eye of his master Lu Ah-cai (who you’ll recall was one of San-Te’s original disciples. In another version of the story, Lu was the disciple of Jee Sin Sim See, the founder of the Hung Gar fighting school (named after his disciple, Hong Hei-gun, who may be Hung Hsi-kuan). Wong refuses to teach his son, Wong Fei-hung (played by Gordon Liu) kung fu, but Lu takes him as a disciple. Wong learns to fight, but more importantly, learns compassion and forgiveness, traits which allow him to defeat and show mercy to a fugitive killer (played by Lau Kar-leung) and lead his school to victory in an annual festival against a rival school with honor.

5. Third Generation: mostly Wong Fei-hung (Late 19th-Early 20th Century):

a. The Wong Fei-hung serials (1949-1970), Martial Club (Lau, 81), the Once Upon a Time in China Series (Tsui Hark et al, 91-97) – Wong is established as a Confucian patriarch, no longer a rebel but an upholder of Chinese values in the face of foreign occupation and rapid modernization. Kwan Tak-hing played him in dozens of films, and these serials provided choreographic and stunt work for both Lau Kar-leung and his father, Lau Cham (who often played Wong’s disciple Lam Sai-wing), as well as Yuen Siu-tien, Yuen Woo-ping’s father, who appeared in the first Kwan Tak-hing film (Whiplash Snuffs the Candle Flame (Wu Peng, 1949) and achieved stardom late in life playing Beggar So. Martial Club sees Wong, played by Gordon Liu, carefully navigating the complex honor imperatives of the martial world to arrive at a bloodless conclusion to a potentially deadly inter-school conflict. The Tsui Hark series, starring Jet Li, envisions Wong as a younger man, but still as chaste and morally ideal hero as Kwan’s older version. He finds himself caught up in the tumult of early 20th Century China, fighting Western imperialists and lunatic Boxers and briefly joining forces with Sun Yat-sen’s Republican revolution. He even finds his way to America to help Chinese laborers in the West.

b. The Drunken Master Series (Yuen Woo-ping, 78; Lau and Jackie Chan, 93; Lau, 93) – Jackie Chan shot to superstardom playing a parodic subversion of the Wong Fei-hung character. A petulant youth rather than an upstanding hero, Wong is taught kung fu by Beggar So (Yuen Siu-tien) in the first film. In the sequel, Wong is still irresponsible, but in a nod to the Tsui Hark series, begins to take action against the imperialists. Lau and Chan had some kind of a disagreement on the set of the film, leading to Lau’s departure, whereupon he quickly made Drunken Master III, in which Wong and his father take on not the Qing, but a local warlord (the film appears to be set sometime after the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911).

c. Rise of the Legend (Roy Chow, 2014) - Wong gets a reboot in the 21st Century with Eddie Peng playing him as a kind of undercover, infiltrating gangs that torment his town’s waterfront. It has more in common with contemporary Triad films like Infernal Affairs or the Election series than the kung fu movies of the 70s, but shows one way the Wong legend continues to adapt to changing idioms.

d. Shaolin Martial Arts (Chang, 74) - Fu Sheng and his pals are students at a Shaolin kung fu school in Canton who fight with a rival Manchurian school. The Manchus bring in a couple of ringers with apparently unbeatable skills to trash their joint and kill some heroes. Retreating to a hiding spot, their aged master sends a pair out to learn new skills from more advanced masters (one of the two is Gordon Liu). There's a long training sequence, which ultimately leads to failure and a repeat of the whole setup, this time another pair finds another pair of masters. This is where Fu Sheng learns from Yuen Siu-tien (an old master who learned his style from Temple refugee Hong Hsi-kuan), while his buddy learns Wing Chun from another guy, in a sequence that Quentin Tarantino ripped off almost completely in Kill Bill Vol. 2.

c. The Boxer Rebellion (1898-1901):

1. The Spiritual Boxer (Lau, 75) – A bit of a detour in the story, as it doesn’t directly involve this particular lineage, but the Boxer Rebellion is nonetheless vital for this history, and for Lau’s films in particular. His first film as a full-fledged director opens with a short prologue in which Ti Lung and Chen Kuan-tai play Boxers, faking their way through a martial arts demonstration before the Empress Dowager. This proves wholly unrelated to the plot that follows, yet it sets a thematic tone for the film and for Lau’s cinema as a whole, that of the dynamic between the fake and the real in martial arts, both in terms of everyday belief and in cinematic representation. Lau’s films will continue the work he’d begun in his choreography for Chang Cheh, that of bringing a greater representational and historical verisimilitude to the martial arts film.

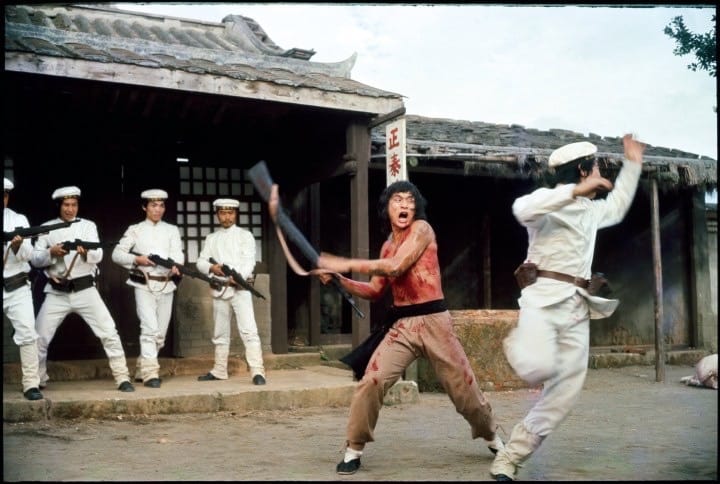

2. Boxer Rebellion (Chang, 76) – Chang Cheh presents a historical epic version of the uprising, in the same year he took the same approach with an older event in Shaolin Temple. Alexander Fu Sheng, Chi Kuan-chen and Bryan Leung (aka Beardy) are fighters who get caught up in the action., They begin as true believers in the movement, but soon come to believe that no matter how developed one’s kung fu becomes, it’ll never actually be strong enough to stop bullets.

3. Legendary Weapons of China (Lau, 82) – Lau Kar-leung himself plays a former Boxer, gone into hiding after he’s discovered the fraud at the core of the movement. Three assassins are sent after him, including Gordon Liu as a Shaolin monk and Lau Kar-wing as a Taoist Magic Fighter. Note that Lau does allow for some degree of magic in a film about how destructive the belief in magical powers is. As always, Lau seeks out a middle ground: yes kung fu can unlock some supernatural powers, but let’s not go crazy and think that makes us impervious to Western firearms.

6. Fourth Generation (Early-Mid 20th Century):

Magnificent Butcher (Yuen & Sammo Hung, 79) and Dreadnaught (Yuen, 81) – The adventures of Wong Fei-hung’s disciples. The first follows Lam Sai-wing, played by Sammo Hung, in his fight against a rival master. Kwan Tak-hing plays Wong, though he’s absent for large portions of the film. Yuen Biao (one of the Seven Little Fortunes Peking Opera troupe, along with Sammo Hung, Jackie Chan, Corey Yuen and Yuen Wah. You can see their young lives dramatized in the lovely 1988 film Painted Faces, in which Sammo plays their master, Yu Jim-yuen) plays another of Wong’s famed disciples, Leung Foon, a role he’d reprise in the first Once Upon a Time in China movie. In Dreadnaught, Beardy plays Leung Foon and he helps Yuen Biao, playing a cowardly laundryman named Mousey, learn kung fu indirectly from Wong himself, played by Kwan Tak-hing for the last time.

7. Fifth and Sixth Generations (Mid 20th Century-Present):

Lam Sai-wing was in real life a teacher of kung fu. One of his students was Lau Cham, who in turn taught his sons Lau Kar-leung and Lau Kar-wing as well as Gordon Liu. Lau Kar-leung, in his work as a choreographer and film director, was instrumental in bringing a new kind of realism into the kung fu film, divorcing it from an older, wuxia fantasy tradition as well as Bruce Lee’s eclectically ahistorical super heroics. Again and again in Lau’s films we see the process of learning, of the transmission of knowledge from one generation to another, and the prizing of tradition as honorable for its own sake. His is nonetheless an expansive conservatism, open to change and adaptation as the times demand it, working to reconcile the male and the female, the new and the old, the secular and the spiritual, the real and the cinematic, history and legend.