Japan Cuts 2025: Part One

Wherein I review Three Kurosawas, Two Serpent's Paths, and One Iwai which stars One Nakayama Miho who plays Two Different Characters

It’s time once again for my favorite film festivals of the year. I’ve covered Japan Cuts for the last couple of years here at The Chinese Cinema (yes I know that sounds weird), and this year I’m going to tackle the New York Asian Film Festival here as well. How will I be able to cover two festivals with literally dozens of movies I want to watch that take place almost simultaneously? I don’t know, I guess we’ll find out!

We’re gonna start here with the archival program for Japan Cuts, which features a couple Kurosawa Kiyoshi movies (Serpent’s Path and License to Live—I’m going to toss Kurosawa’s recent remake of Serpent’s Path in here as well) and Iwai Shunji’s Love Letter.

The original Serpent’s Path was released in 1998, and stuck to the lo-fi style of Kurosawa’s early V-Cinema productions, though it did receive a theatrical release. The 2024 remake was filmed in France with a bunch of famous French actors. The two plots are essentially the same: a man and his partner kidnap someone who they believe is responsible for the torture and death of the man’s 8 year old daughter. After chaining their victim up in an abandoned warehouse and engaging in some light torture, they become convinced that their victim may not be the true culprit, and so they kidnap another guy. And then another, slowly unraveling what appears to be a criminal conspiracy, while the man himself too unravels, putting in to question every aspect of his demented mission. In the 1998 version, the man is abetted by a bespectacled figure of eerie calm, who in flashbacks is revealed to be a kind of advanced math teacher. In the French version, the helper is a woman, who in flashbacks is revealed to be a psychiatrist. In both cases the flashbacks undermine our understanding of the reality of the present, though in very different ways that probably says something about the differences between the underground Japanese cinema of the 90s and the prestige French cinema of the 20s.

Aikawa Show, a longtime staple of Kurosawa and Miike Takashi features, plays the teacher. In dealing with the potential criminals, he is ruthless and dispassionately efficient (he reminded me of an affectless Kitano Takeshi gangster). But in both the flashbacks, and in what appear to be present-day scenes of him teaching his math class, he is recognizably humane. The doctor in the remake is played by Shibasaki Ko, and she’s a softer, more emotional figure. Her flashbacks circle around her treatment of a fellow Japanese expatriate played by Nishijima Hidetoshi (Drive My Car), who is lonely and depressed living in France. A Japanese director working in France on a movie about people who are suicidally/homicidally depressed about being Japanese people living and working in France seems a little on the nose for Kurosawa, but I’ll allow it. One thing that every great filmmaker seems to treasure as their style gets older is simplicity: making the subtext text.

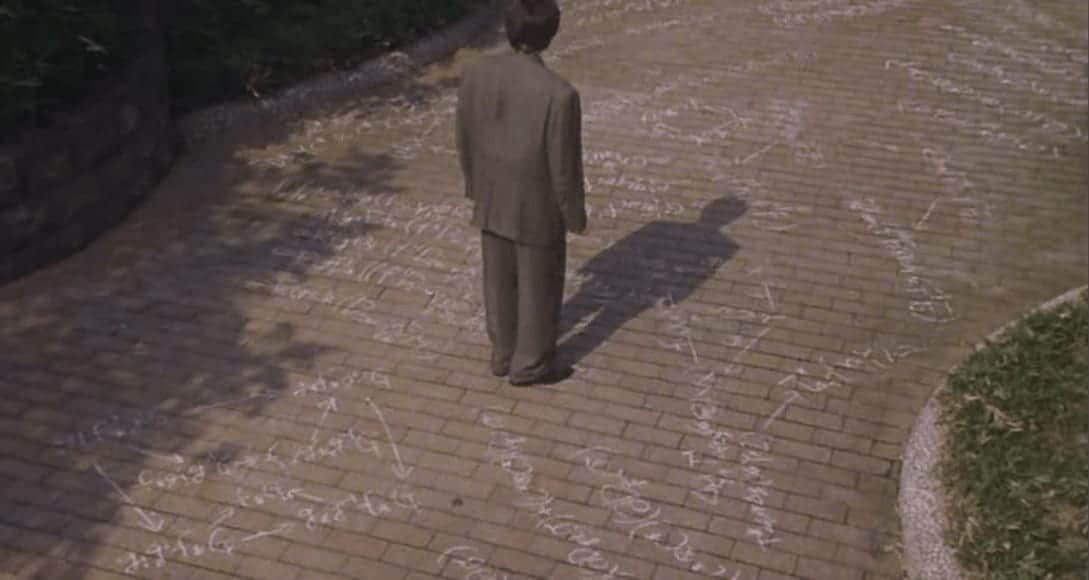

The original though, made when Kurosawa was a much younger man, revels in ambiguity. In the 1998 film, we see Aikawa and his partner meet in what appears to be the first time, as Aikawa and his daughter are working on complex math equations with sidewalk chalk. In the middle of the kidnapping, we follow Aikawa to his class, where a precocious little girl who looks an awful lot like both his daughter and the other guy’s daughter, is quick to offer solutions to various problems. Though not always correctly: one answer he warns will have deleterious effects on both space and time were it to turn out to be correct. Is this all the same girl? Did the kidnapper ever have a daughter at all? Are there ghosts? These are the kinds of gray spaces the 1998 film lives in, the eerie sense of uncanny evoked by Kurosawa’s use of smooth long takes, off-screen sound, and unpredictable acting direction, the hallmark of the kinds of films that made him famous.

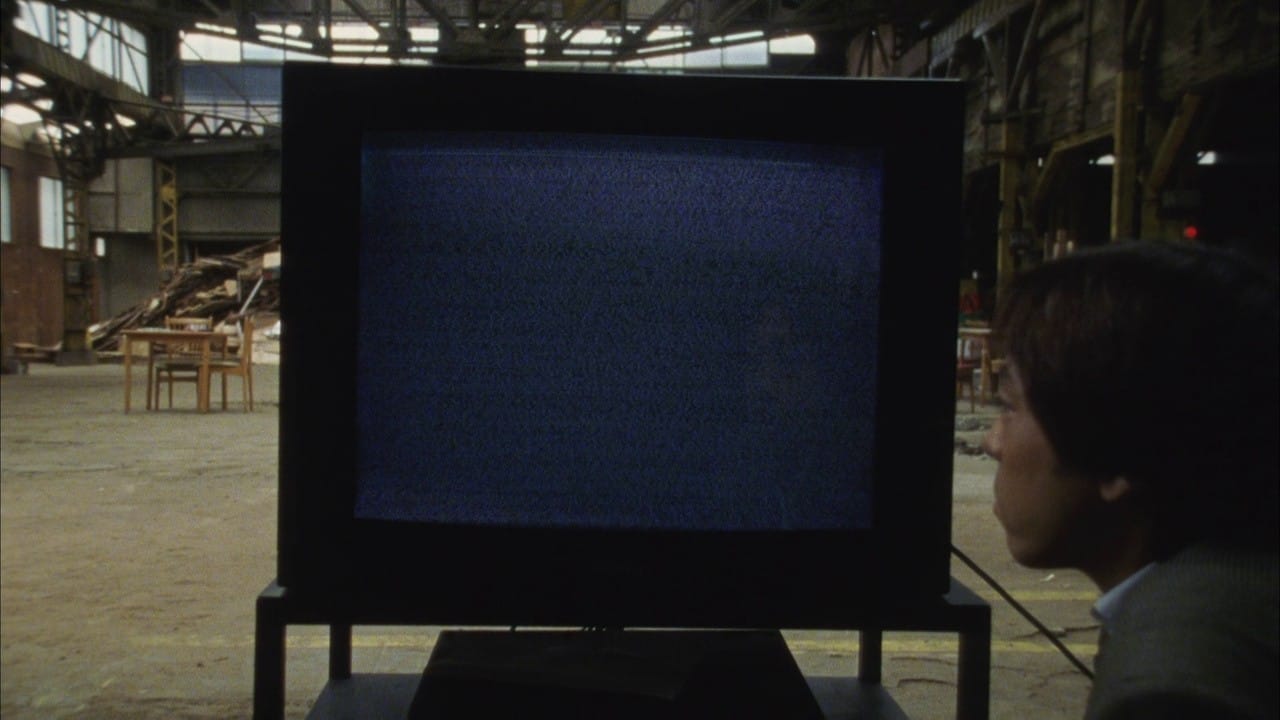

The remake is more, well, psychological, ultimately providing a more or less grounded explanation for its world, in keeping with the expectations of modern art house cinema. It’s littered with famous faces (Mathieu Almaric and Grégoire Colin, in addition to Nishijima) and everything is clearly spelled out. The 1998 film leads us into a vast criminal conspiracy of ever weirder villains, and its central crime is one not just of murder but of ghastly rape and violence, consumerized in the form of videotapes for the demented audiences. In the remake, the bad guys are more banal, and their murders are more clinical: rather than sell images of children being brutally abused, they harvest their organs for the black market, blood and body parts for the sake of the amoral rich, extending their lives with the souls of the young.

While films like this, movies of unease, have been Kurosawa’s calling card throughout his career, many of his best work falls in other, non-violent genres. 1999’s License to Live is one such film. Lying somewhere between an inspirational family drama and a black comedy, it’s about a man who wakes up after years in a coma. He was 14 when he was hit by a car, and 24 when he awakes. Nishijima Hidetoshi plays the man (the most uncanny thing in the film is seeing traces of the middle aged Nishijima of recent years in this young kid), and Yakusho Kōji (who looks pretty much exactly the same now (in films like Perfect Days) as he did then) the man who picks him up from the hospital and brings him home.

We eventually learn that Yakusho is a friend of Nishijima’s father and that, in the wake of his accident, the family split apart: his father traveling the world doing charity work, his mother working at a shop in the city, his sister, rumored to have gone to America, shacking up with Aikawa Show (again bespectacled, but otherwise a much nicer guy here than in Serpent’s Path). Yakusho is living on the family’s sizable exurban property, running a fish farm where city folks can sit around a tank in a warehouse and try to catch carp, pretending they’re in the wilderness, and generally using it as an illegal dumping site for various bits of industrial junk and detritus.

Nishijima, suddenly an adult without the intervening decade of psychological maturity that usually (thought certainly not always) comes with physical maturation, finds himself a man out of time. He tries to reconnect with friends from school, but they’ve grown up without him and drifted away. He tries to reunite his family, all of whom have moved on and aren’t really sure how to reintegrate him, not to mention each other, into their lives. Remembering a time in his childhood when the family ran a small “dude ranch” (pony rides around a small pen for city folk), he reconstructs it, complete with a snack stand and milk bar for the weary travelers. It’s an idyllic spot, which Kurosawa shoots with magic hour beauty and calm joy. But Nishijima is still unsatisfied: reliving the dreams of youth is no way to grow older.

Iwai Shunji’s Love Letter suggests just the opposite however: that looking back is often the way forward. This was Iwai’s debut feature, coming after directing a few successful TV projects like Fireworks, Should We See It from the Side or the Bottom?, an apprenticeship seems similar too, but is really quite different from the one Kurosawa had, working his way up through the grime of pink film and V-Cinema. Though Kurosawa is only a few years older, their styles and sensibilities couldn’t be further apart. Iwai, at his best, is a master of melodrama, at making beautiful images that express and evoke powerful emotions scored with tasteful, and sometimes lightly experimental, music. He’s also the greatest epistolary filmmaker we’ve ever had, reaching back for his plots and psychologies beyond the kind of naturalist 19th century fiction that dominates so much of our understanding of character to an older, more freewheeling tradition.

Nakayama Miho plays a woman named Watanabe Hiroko who is mourning the death of her fiancé, who fell two years earlier while climbing a mountain. Looking through his old junior high yearbooks, from a time before she knew him, when he lived in Hokkaido, she finds his address and writes him a letter, not expecting it to be delivered anywhere (his mother has explained that their home is now a highway). To her great distress, she receives a reply. It’s from a woman who shares the same name as the fiancé (“Fujii Itsuki”) and who was in the same class as him and who is also played by Nakayama Miho. Unraveling this comical mix-up takes up the first half of the film; the second is predominated by flashbacks, in which the Woman Itsuki writes letters to Hiroko in which she relates memories of Boy Itsuki. We see these played out as another actress, Sakai Miki, plays Girl Itsuki as a junior high student. So that’s three different actors playing characters named “Fujii Itsuki,” two of whom are the same person separated by time, and one actress playing two different characters with different names, who are separated by hundreds of miles of space (Hiroko lives in Kobe; the two almost meet a couple of times, but it doesn’t actually happen, which is probably for the best—the effects would probably be deleterious for both space and time).

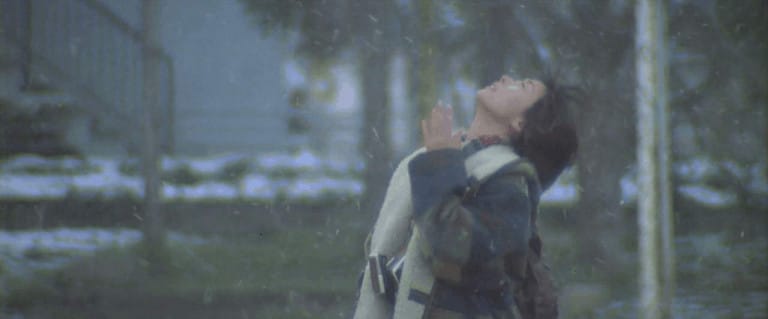

Much of the plot involves standard non-romantic drama material: the family home is threatened by modernity; an illness and a blizzard may conspire to cause an untimely death, but the heart of the film is its intertwined romances. There are Hiroko’s attempts to come to terms with Itsuki’s death, nudged not quite gently along by her current, glass-blowing boyfriend, one of Man Itsuki’s best buddies. And more intriguing, and almost as painful, is Woman Itsuki’s dawning realization, as she excavates her own memories, that Boy Itsuki may have been in love with her all along. As Hiroko too comes to suspect this (and notices Girl Itsuki’s resemblance to herself) she wonders if Man Itsuki loved her, or just the fact that she looked like Girl Itsuki. Are adult romances mere shadows of adolescent crushes? Is her relationship with her current fiancé simply the closest thing she can find to the man she really loves? Is it even possible to let go of the past and move into the future, and if it is, would we really want to?

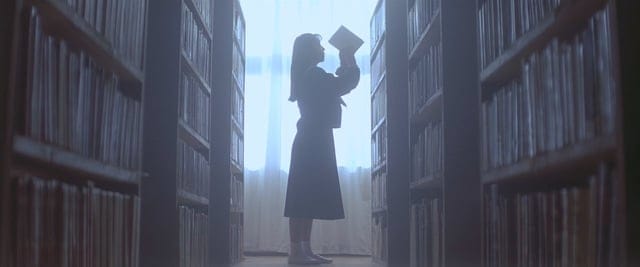

Iwai approaches these questions with a light charm and heavy emphasis on aesthetic beauty, a hallmark of his greatest work, from 1998’s April Story to 2023’s Kyrie (a highlight of last year's Japan Cuts), and Nakayama’s performances are equally lovely. He shoots Hiroko’s scenes with a severe coldness, modern edges and gray light, the tastefulness of class and adulthood, while Woman Itsuki’s world (her family home, the public library she works at) is a whirl of soft light chaos, warms browns and fuzzy scarfs. They’re two halves of the same woman, the same world, united only by the memory of a person who no longer exists, but whose life lingers on.