Ghost Killer (Sonomura Kensuke, 2024)

Ever since I learned of the existence of Ghost Killer, about a year ago now, it has been my most anticipated film. Now it’s opening here in the US (on digital first and then on 4k and bluray), thanks to the fine people at WellGo USA, and I simply had to take time out of my festival binge to catch up with it. Takaishi Akari stars as a college student and beleaguered waitress who suffers through a meetup with a boring guy in the hopes of connecting with a social media influencer. On the way home, shortly before meeting a friend who has been beaten up by her boyfriend, she picks up a bullet casing and becomes inextricably linked to the ghost of a professional assassin. The killer can possess her body, giving her the power to fight bad guys, which they do over the course of a very long day: protecting her friend, punishing the guys who try to drug and assault her, and finally taking on the criminal organization that had the assassin murdered. It’s basically Where’s Officer Tuba? but played straight and put together by some of the hottest makers of action cinema anywhere in the world right now.

Takaishi is, of course, one of the eponymous Baby Assassins in the series of three films and a TV series written and directed by Sakamoto Yugo and choreographed by Sonomura Kensuke. Sonomura directs and choreographs Ghost Killer, from a Sakamoto script. He’s directed before, with the movies Hydra and Bad City, which lack the cleverness of Sakamoto’s stories but make up for it with a genuine affection of the gangsters and killers he finds on the margins of society and then puts through incredibly athletic and brutal brawls. Sonomura’s direction is as physical as his choreography: every movement has a purpose, even the feints. It serves him well in the spaces between the fights, as Takaishi struggles with being an ordinary girl tossed against her will into a Wickian world of amoral killers.

In the Baby Assassins films, Takaishi is the less athletic of the pair, routinely taking a backseat to Izawa Saori during the peak fight scenes. She moves well on camera and gets by just fine, but she’s an actor first, not a stunt person (she's done a lot of work in regular (non-action) films and television). Thus she anchors the non-fight scenes in those movies, being the more verbal, expressive one of the pair, using her large eyes and big smile to great effect in conveying the films’ deadpan depiction of slacker sociopaths. She’s terrific in Ghost Killer as well, anchoring the fantastical scenario in real-world emotions–panic, fear, disgust, anger–that she struggles to control but which the killers have left behind them long ago. It’s not as meta a twist on the genre as most of Sakamoto’s other work (Yellow Dragon’s Village for example, or even A Janitor, where Takaishi and Izawa were first paired), and as such makes for maybe his most relatable film yet. Likewise Takaishi brings a humanity to Sonomura’s choreography that those earlier features lacked, with their worlds of sad men splitting heads and firing bullets.

Mimoto Masanori plays the Ghost as just such a sad man. Disillusioned with the turn his company has taken under new ownership, he gets killed for growing a conscience. A veteran of both Hydra and Bad City (as well as Miike Takashi’s Yakuza Apocalypse and First Love and the terrible Donnie Yen film Enter the Fat Dragon). As Mimoto is possessing Takaishi, Sonomura cuts freely between the two in their fights. Basically, whenever something really athletic is called for, we see Mimoto do it. This approach peaks in the finale, when they storm the enemies lair and faces dozens of anonymous bad guys. Sonomura tracks one, and then the other, as the fire, punch and kick their way through the bad guys, using invisible cuts and wipes to flash from one actor to the other. Mimoto takes center stage for the final brawl, which, though he doesn’t have the charisma of Izawa, is a top-notch Sonomura brawl: punching and grappling and very real physical pain.

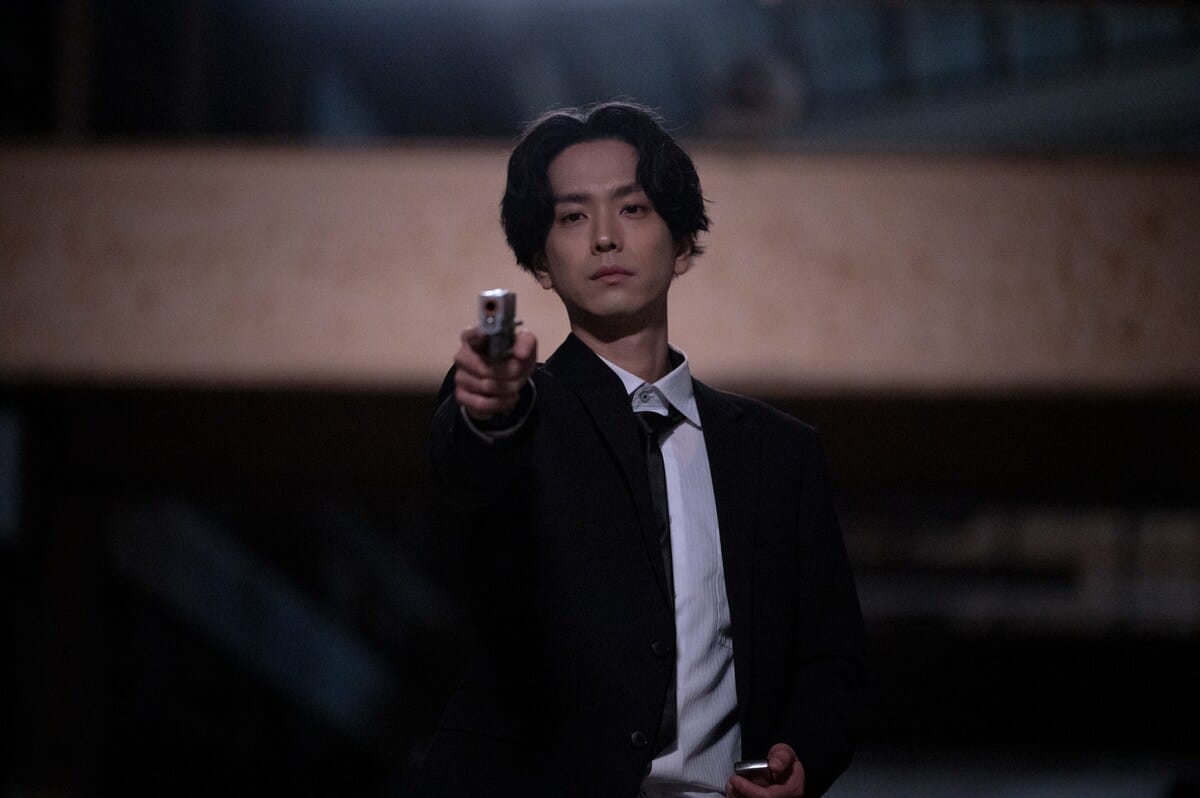

Joining the two heroes on their quest is the Ghost’s former protégé (Mario Kuroba), a younger killer who reluctantly helps them out and, like the Ghost before him, seems to grow a conscience. Sakamoto’s scenario sees a parallel between these killers, men who have been trained to be merciless killing machines from a young age (their ranks within the organization are based on dog names, a parallel between canine and killer dating back at least to Jet Li in Louis Leterrier and Luc Besson’s Unleashed (aka Danny the Dog), and the way Takaishi becomes possessed by the killer. Not too much is made of the metaphor, but it works to show how observing her experience can turn these lost men into, for a time at least, some kind of heroes.