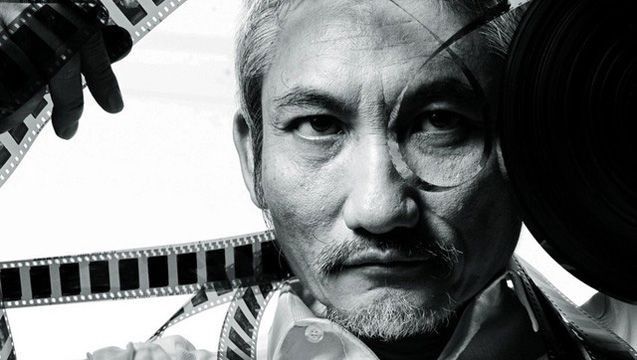

Once Upon a Time in Hong Kong: The Cinema of Tsui Hark

Tsui Hark has been the central figure in Hong Kong and Chinese language cinema for the past 40 years, responsible for at least a dozen different masterpieces as director and/or producer. He’s often likened to Steven Spielberg, though more for the universal popularity of his films and their technical achievements; artistically, no one is really much like him at all (surely the mark of a great director). Names like John Ford and Howard Hawks come to mind for his humor, his sense of history, and his generic profligacy, but they don’t capture the visceral anger of Tsui’s anti-establishment statements, the centrality of women and the fluidity of gender in his work, or his obsession with pushing the technology of cinema forward, not in the service of verisimilitude, but in the desire to capture the wildness of imagination. After 50 films as a director, and many more where he was credited as producer but served as the primary creative force, Tsui is still expanding the medium, still working regularly and making some of his best work.

Born in Canton and raised in Vietnam, Tsui attended high school in Hong Kong and then went to Texas for college, first at Southern Methodist, and then at the University of Texas in Austin, where he studied film. After a brief period working on documentaries in New York, he returned to Hong Kong in 1976 and began directing in television. In 1979, he made his feature film debut with The Butterfly Murders, a low-budget, highly unconventional wuxia with elements of mystery, horror, and sci-fi and a strikingly modern visual style and approach to narrative (yes, it’s about homicidal butterflies). He followed it up the year after with We’re Going to Eat You, a comic kung fu detective story about cannibals. Later the same year, he released Dangerous Encounters — First Kind, a nasty, incendiary contemporary drama about nihilistic teenagers who set off a series of bombs for fun and run afoul of a gang of American arms dealers. These three films, along with a handful of others released by young directors who, like Tsui, studied film abroad and worked in local television (Ann Hui, Patrick Tam, Allen Fong, Yim Ho), flipped Hong Kong cinema on its ear with a series of low-budget, politically-committed reinventions of traditional Hong Kong genre films, taking them out of the ornate sets of the Shaw Brothers and Golden Harvest studios and into the chaotic city streets, reflecting both the influence of the European and American avant-garde and the complex of contradictions within the colony itself, specifically in the breakdown of its administrative, social, and familial institutions. Inevitably dubbed the Hong Kong New Wave, they met with much notoriety and critical acclaim but little box-office success, and eventually they drifted into the mainstream. Again Tsui led the way with his fourth film, a slapstick detective farce called All the Wrong Clues (…For the Right Solution) made for the Cinema City studio, which gave Tsui his first hit. But the spirit of these early films, with their experimentation and uncompromising punk attitudes would never disappear from Tsui’s cinema, as even his most popular works would contain at least a little bit of contempt for established authority.

For his next film, Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain, Tsui imported Hollywood special effects experts for a phantasmagoric fantasy wuxia built around Chinese folklore and told with a dizzy rapidity, in both narrative and action. It launched a whole subgenre of wuxia films, in which godlike kung-fu experts fly around shooting chi energy and battling demons and gods in blindingly-cut hyper-colors. More comic-book than Chang Cheh’s stately tales of chivalry and brotherhood, it was a hit, and would later inspire John Carpenter’s Big Trouble in Little China.

In 1984 and 1986, respectively, Tsui directed two of the best films of the 1980s, Shanghai Blues and Peking Opera Blues. In the former, Kenny Bee and Sylvia Chang are a young couple who meet briefly, fall in love instantly, and are torn apart in the dark of the Japanese bombing of their city at the start of World War II. After the war, they unwittingly become neighbors in the overcrowded city. Sally Yeh plays a young refugee who befriends them both as the film explores a world caught in-between a disastrous past and a fearful future, where everyone is either trying to become a star or remain hidden from those who would do them harm. With carefully choreographed comic set-pieces in the vein of Chaplin and Keaton, and recalling both the Mandarin sing-song films of the ’30s and American screwball comedies, it might be Tsui’s best comedy — though its companion gives it stiff competition. Set in the years just before the Japanese invasion, Peking Opera Blues follows a trio of women (Brigitte Lin, Cherie Chung and Sally Yeh) who get mixed up in a scheme to steal an important something from a local warlord. With deft action and comic sequences and a shockingly progressive (certainly for Hong Kong cinema in the ’80s) feminist approach (led by Lin’s gender-nonconforming heroine), Peking Opera Blues is as close to perfect as the popular cinema gets.

Also in 1986, Tsui found John Woo depressed and drinking too much, his career floundering, and produced his dream project, A Better Tomorrow, which became a massive hit, made Chow Yun-fat a superstar, and launched the “heroic bloodshed” cycle of gangster films. Tsui and Woo fell out over the editing of that film’s 1987 sequel, though, but unhappily worked together again on Woo’s 1989 masterpiece The Killer. When it came time to make A Better Tomorrow III (later in 1989), Tsui went off and made it on his own, leaving Woo to direct his version of the story for another company under the title Bullet in the Head. The difference between the two films neatly shows the primary differences between Woo and Tsui as directors: Tsui’s film is female-centered, with Anita Mui playing a badass woman who shows Chow Yun-fat not only how to shoot a gun, but inspires his iconic outfit (trenchcoat, sunglasses, matchstick); Woo’s epic is a tale of brotherhood gone bad, the only woman an object to be rescued by our heroes. Woo’s film is a Catholic tale of blood and guilt, his characters’ anguish externalized in pop music and fluttering doves, tears and car chases and handguns that never need to be reloaded. Tsui’s is relentlessly materialist, his characters not avatars for Good or Evil or Greed or Betrayal, but living humans with conflicting motives and complex personalities.

At the same time he was working (more or less) with Woo, Tsui produced A Chinese Ghost Story. Directed by Ching Siu-tung and starring Leslie Cheung and Joey Wang, it’s an adaptation of a story from the 17th century collection Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio. Tsui and Ching bring this venerable material into the present with advanced special effects and a cock-eyed sense of humor and horror inspired by Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead series. It was another critical and popular hit and inspired a series of sequels, including, a decade later, one of the first Chinese animated films to incorporate 3D CGI. In 1988, Tsui produced Johnnie To’s first contemporary crime film, The Big Heat, which wasn't very successful but gave a glimpse of To's theretofore unrealized talents; and in 1990, he attempted to revive King Hu’s career with The Swordsman. It didn’t work: Hu walked out before filming even began and the film was finished by Tsui and Raymond Lee (with an assist from Ann Hui and others). Its highly popular sequels, Swordsman II and Swordsman III: The East is Red, were produced by Tsui and directed by Ching Siu-tung, and featured Brigitte Lin’s iconic Asia the Invincible, a kung-fu master whose drive for perfection changes them from a man to a woman. Tsui’s most sophisticated fantasy wuxia was 1993’s Green Snake, a reimagining of the legend of two snake sisters whose kung fu is so advanced they become human. The typical story follows the White Snake, who becomes infatuated with a young monk, but Tsui focuses on the other, whose interactions with a fanatical monk convince her that being human, with its irrational rules and sexist establishment, is actually much worse than being a snake.

As generic reinventions go, Tsui’s most important came in 1991 with Once Upon a Time in China, a new take on folk hero Wong Fei-hung, subject of over a hundred films since the 1950s. A massive hit, the film inspired five sequels, made Jet Li a superstar, and almost single-handedly revived the period kung-fu film, all but forgotten in the late ’80s after the collapse of Shaw Brothers and overshadowed by policiers and fantasy films. More than that, the Once Upon a Time in China films (along with their prequel spin-off Iron Monkey) present the fullest expression of Tsui’s Fordian vision of Hong Kong’s past, a desire to reconcile the conflicting forces that threaten to tear the colony apart, trapped as it is between the modern West and the traditional East. Tsui’s Wong is an upstanding young man of Confucian virtue who must do battle with imperialists enslaving Chinese workers, fanatical Boxers, corrupt government officials, and criminal gangs, while, with the help of his more Westernized friends, learning to adapt to new ways at the end of the 19th century. The in-betweenness of Hong Kong in the years between the 1984 Joint Declaration and the 1997 Handover is a powerful subtext of much of the colony’s cinema during that era, as in the apocalyptic action films of Ringo Lam. With these Wong Fei-hung films, Tsui seems almost hopeful that the contradictory forces might be reconciled.

But there’s no hope to be found in 1995’s The Blade, a remake of Chang Cheh’s seminal The One-Armed Swordsman. Released a year after Wong Kar-wai’s lush, oblique wuxia Ashes of Time, The Blade is a black blur of insanity, a hellscape of psychotic gangs terrorizing miserable peasants, where a hero rescues a damsel in distress not out of chivalry, but out of a guttural lust to possess. Chang’s film brought a new darkness to wuxia, leading to a decade of very serious films about men tortured physically and psychologically by the demands of honor and brotherhood. By the late ’70s, though, such films had been superseded by the lighter action films of Sammo Hung, Yuen Woo-ping, Corey Yuen, and Jackie Chan. With the pendulum swinging back again, Tsui countered the comic kung-fu films with a vision even more nihilistic than anything Chang could have imagined, exuding a darkness no martial arts filmmaker has yet successfully matched. Befitting his contradictory nature, in this same year Tsui also directed two bright slapstick comedies: The Chinese Feast is a cooking-competition film about art and family; while Love in the Time of Twilight is a screwball twist on Back to the Future, Ghost, and Looney Tunes cartoons. It joins the previous year’s The Lovers, a rom-com farce turned hallucinogenic melodrama based on the classic “Butterfly Lovers” tale, as Tsui’s most beautiful romance.

In 1997, Tsui joined Woo, Lam, and others in Hollywood, where he directed a pair of immensely fun Jean-Claude Van Damme vehicles, Double Team and Knock Off. The movies weren’t particularly successful, critically or commercially, and Tsui returned to Hong Kong in 2000 for Time and Tide, a contemporary action film about a young bodyguard who gets caught up in a war between an honorable assassin and his old employer. It ends up not only being a moving meditation on fatherhood, but also features some of the best fights of the 21st century, a perfection of the aesthetic of speed, where the editing doesn’t obscure performance, but amplifies it beyond the possible.

The rest of the 2000s proved less successful, with a CGI-heavy remake of Zu Warriors proving more lovely than compelling, and the epic war film Seven Swords suffering from being condensed to a mere two-and-a-half hours. 2008 brought the clever screwball All About Women and the lovely ghost melodrama The Missing — but it was with 2010’s Detective Dee and the Mystery of the Phantom Flame that Tsui seemed to regain his old form. Based on a series of 20th century stories inspired by a 19th century novel based on real figures from the 7th century Tang Dynasty, Detective Dee and a 2013 prequel, Young Detective Dee: Rise of the Sea Dragon, revolve around the hero’s efforts to defend Empress Wu (Carina Lau), the enigmatic ruler generally demonized throughout Chinese history but somewhat rehabilitated in Tsui’s version. The films are packed with action and outsized computer effects, among the best examples of the digital aesthetic now common in Chinese film.

In-between the two came Tsui and China’s first digital 3D film, Flying Swords of Dragon Gate, a variation on King Hu’s 1967 classic Dragon Gate Inn (which Tsui also had remade in 1992 with Raymond Lee as the credited director) that recasts the film as a fantasy blockbuster bearing an unmistakable resemblance to Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. And in his latest film, 2014’s The Taking of Tiger Mountain, Tsui uses 3D and CGI to reimagine one of Mao’s Model Operas from the Cultural Revolution, a tale of wartime heroism (the People’s Liberation Army captures a Nationalist outpost during the Civil War), as a modern blockbuster, pointedly draining all the politics out of a famous work of propaganda and leaving us to examine what, if anything, is left behind. Deftly negotiating the demands of the Chinese censorship apparatus while subtly subverting that system in the context of a wildly entertaining action movie, Tiger Mountain shows Tsui’s enduring commitment to reconfigure old forms and push cinema into the future.