The Shaolin Kids (Joseph Kuo, 1975)

Like Joseph Kuo's Shaolin Kung Fu, this has very little to do with the mythology around the Shaolin Temple, nor does it feature any kids, at least of the non-grown up variety. Nor is it a kung fu film in the vein of the Shaolin cycle Chang Cheh and Lau Kar-leung were exploring at the same time over in Hong Kong. Instead, it’s a wuxia historical epic along the lines of Chang’s The Heroic Ones that is deeply indebted to the early films of King Hu. In the way that Shaolin Kung Fu remixed elements of Bruce Lee films like The Big Boss and Fist of Fury, Kuo here borrows one of the stars (Polly Shang-Kuan Ling-Feng) and the milieu of Ming Dynasty political intrigue from Dragon Gate Inn, along with the serial protagonist structure of that film and Come Drink with Me (one of the villains even asks Shang-kuan, at one point, to “Come drink with me”).

The Prime Minister plots to overthrow the Emperor but is discovered by a loyal official. He has the official killed, but not before his daughter escapes with a secret letter the Minister is sending out to enlist support for his evil plan (his support eventually comes mostly from outside forces like the Japanese and the Mongols). She gets the help of her father’s friends, along with the head of a lay branch of the Shaolin Temple that is devoted to fighting corruption in the Empire with kung fu. Through many twists and turns of the espionage plot, the loyal elders are picked off one by one until only the young woman and the son of a top general, who had been studying at Shaolin, remain. These are, I suppose, the eponymous Shaolin Kids.

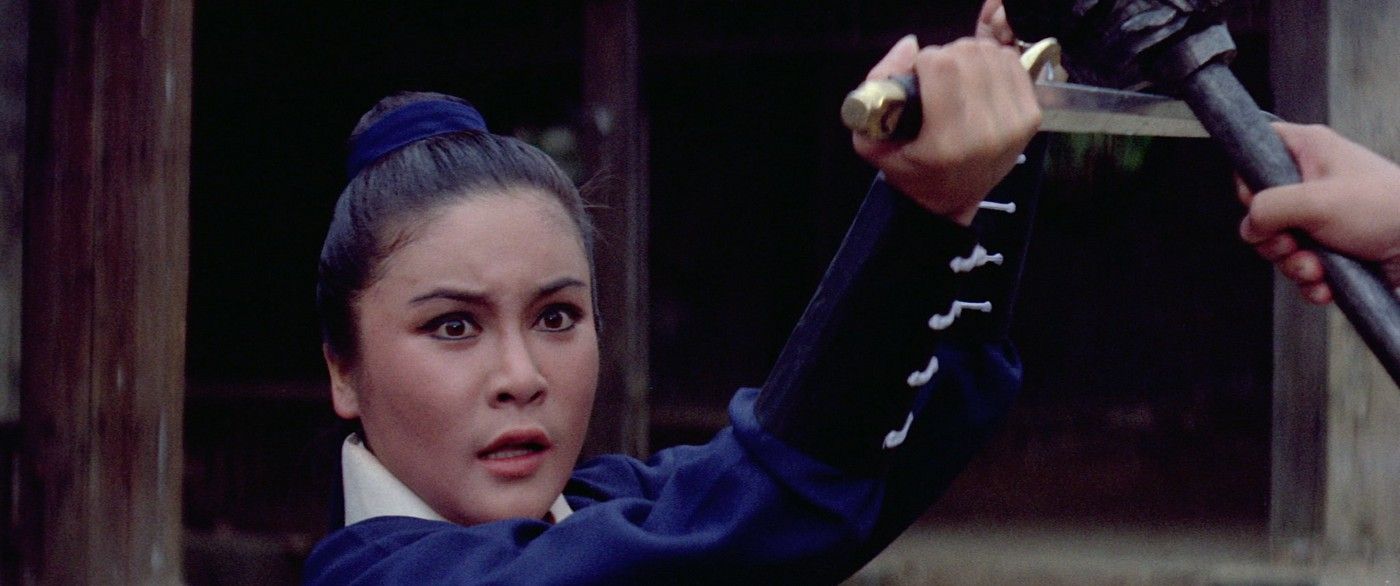

The film is an almost non-stop series of fights, as the heroes come up with a plan and are foiled by the Minister’s agents again and again. The fights are of the older variety: trampoline jumps with cuts to bodies flying through the air in the King Hu style, big group sword fights, and not much in the way of punching and kicking. They’re all very good, but they lack the grace of Hu’s work, the balletic interplay between movement, editing, and music that makes those films the masterpieces they are. But at the same time, Kuo keeps Shang-Kuan in the center of the narrative, unlike Hu, who pushed her aside in Dragon Gate Inn like he did with Cheng Pei-pei in Comes Drink with Me, in favor of their male co-stars. She’s the prime mover of Shaolin Kids’s narrative, and while she’s joined by a variety of men, they’re always in support of her, not the other way around.

Similarly, Kuo takes a more nuanced approach to his villain. Rather than the irredeemable evil of Hu’s villains, Kou’s Minister is given a very human motivation: the Emperor has ordered him to kill his own son. Granted, it’s because the son murdered two innocent civilians, but still, a father’s love and all that (this was also the villain’s motivation in Shaolin Kung Fu). As he receives his final comeuppance, one almost feels bad for the guy, which isn’t something anyone could say about the demonic monsters in human form that haunt Hu’s films. Just as he eschews the spirituality underlying the connection between kung fu and Buddhism in its Shaolin form (he doesn’t even give us a monk, there’s a Taoist priest, but he turns out to be a traitor too), so Kuo grounds his fight between good and evil in the moral gray areas of real life.