The Once Upon a Time in China Series

With the fall 2021 release of Criterion’s Once Upon a Time in China boxset, I put all my reviews of the series together here in one convenient place.

Once Upon a Time in China (Tsui Hark, 1991)

Tsui Hark is the John Ford of Chinese cinema, and Once Upon a Time in China is his Stagecoach. Not only does it redefine a genre on the cusp of its rebirth (in this case the period martial arts film, which had lain dormant through the late 80s much as the Western had been relegated to cheap serials through the 30s), but it expresses a total historical vision entirely through archetypes, which are by turns deepened and confounded. Much has been made of the film’s nationalism, an apparent sharp turn from the more scathing works of Tsui’s New Wave films, but like Ford, Tsui’s patriotism is more complex than it appears on the surface.

Set at some point in the late 19th Century, we find Wong Fei-hung’s city of Foshan (on the Pearl River Delta, just northwest of Hong Kong) in turmoil. The crumbling Manchurian government is both corrupt and weak and at the mercy of Western powers, represented here by a cadre of Americans (wearing Union blue but speaking in the Southern accents Tsui must have heard as a student in Texas). The Americans are recruiting Chinese laborers with dreams of gold, poor men who quickly learn that they’ve unwittingly sold themselves into slavery, one escaped man’s account of the passage to and life in America eerily reminiscent of the narratives of another people sold into bondage in the States. Wong is the leader of the city’s militia, and also a renowned doctor. His father, Wong Kei-ying, according to tradition a famous anti-Manchu freedom fighter, is notably absent from the story, and Wong gets along well with the local military commander, but there’s an underlying layer of tension: the Mandarins don’t trust Wong, but it isn’t because of his status as a Han hero, or Ming Dynasty die-hard, as in earlier versions of his story, but rather because of his incorruptibility.

The upstanding morality that makes Wong a hero to his disciples and a threat to the villains sets him at odds with certain members of his circle, most notably his 13th Aunt, played by Rosamund Kwan (she’s roughly the same age as Wong, and is the daughter of his great uncle (the number specifies that she is Wong’s 13th oldest aunt), though technically she’s no blood relation — the details aren’t really clear in the translation). She’s returned from two years abroad and now speaks English, wears Western dresses, and lugs around a giant camera. She and Wong are obviously in love, but neither manages to find the right time to tell the other: it’s the kind of awkward, chaste romance that best fits Jet Li’s weird non-sexual charisma. The other member of Wong’s circle to show a Western influence is “Buck-Toothed" So, played by Jacky Cheung, a Chinese-American who has come to Foshan to study medicine under Master Wong. So stutters terribly when he tries to speak Chinese, and can barely read the language, but speaks English with a loquacious fluency. In humanizing and undermining a pernicious racist caricature, Cheung’s performance recalls the Ford characters played by Stepin Fetchit in the Judge Priest movies.

Rounding out the ensemble are Lam Sai-wing (“Porky Wing”), Wong’s eldest student, a fiery pig butcher (based on a real person: Lam was the man who trained Lau Kar-leung’s father in kung fu), and Leung Foon, played by a vastly overqualified Yuen Biao. Leung works for the local theatre, and has dreams of making it big on stage, but gets into trouble with a gang that demands protection money. He flees through the town and he and Porky end up fighting the gang together, destroying much of the town and ultimately bursting into the Western hotel where Wong is having lunch with the Manchu commander and the evil Yankees. This gets the militia arrested, makes Wong a target for the authorities, the Americans, and the gang, which resorts to increasingly devious and violent means to revenge themselves on him.

The gang’s various attacks on Wong bring in two bystanders. The first is an elderly white Jesuit who is the only man in town willing to support Wong in his efforts to arrest the gang leader: no one else, Chinese or otherwise, is brave enough to bear witness. Later, the Jesuit will sacrifice himself to save Wong’s life, leaping in front of a bullet aimed at the hero’s back. The other is a down on his luck martial arts master named “Iron-Vest" Yim. Reduced to performing for spare change on the streets, poverty ultimately twists his moral code to the point that he’s willing to ally himself with the gang and kill Wong in order to earn the money to start his own school, in the kind of “a little bad now for a lot of good later” rationale that many of my friends recited to themselves when they entered law school.

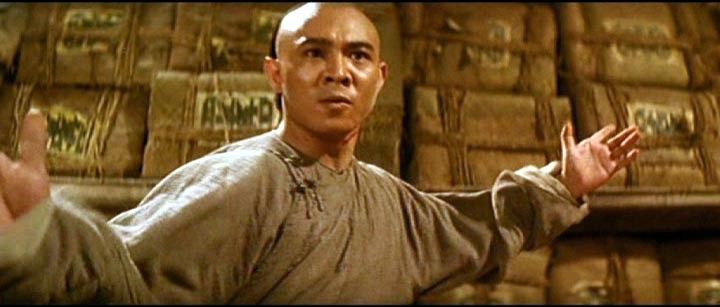

So here we have the array of contradictory forces tearing China apart in the late 19th century: forces of modernization and tradition, Chinese and Western, forming the background for a heroic myth, the story of a man brave enough to stand up for righteousness, even at the cost of his personal happiness. It’s the scope and context of Tsui’s film that sets it apart from other martial arts hero narratives, just as the encapsulation of an entire society in a rolling box sets Stagecoach apart from the oaters that came before it. Far from the mischievous or petulant youth of the previous 15 years of Wong Fei-hung films, like Lau Kar-leung’s Challenge of the Masters or Yuen Woo-ping and Jackie Chan’s Drunken Master, or the Confucian patriarch Kwan Tak-hing played in dozens of serials in the 1950s and 60s (the theme song of which is an essential part of all Wong films, of course Miramax excised it from their releases of Iron Monkey and Drunken Master II), Jet Li’s Wong is both youthful and wise, a serious young man with a code, not at all the free-drinking goofball he played in the Fong Sai-yuk or Swordsman movies. Befitting the ideal, he always seeks to avoid conflict and violence, but when trouble breaks out, he carries himself with supreme confidence: he’s the greatest fighter in any room and he knows it, but he takes no joy in it, and similarly no anger. When breaking up the fight in the banquet, using Kwan’s trademark umbrella to capture the gang leader, Wong holds back, he fights to contain, not to kill. And when the Americans turn their guns on an audience of innocents during a gang attack at the theatre, Li for the first time makes Wong truly his own: departing from the Hung Gar kung fu style the historical Wong popularized throughout Southern China and incorporating elements of his own Northern Chinese wushu forms (to simplify extremely: more kicking, less punching).

The break in authenticity is expedient of course, though it would drive Lau Kar-leung nuts (reportedly the source of conflict between Lau and Jackie Chan on Drunken Master II was Chan’s improvisation on traditional styles) along the lines of the wire-fu Tsui and Ching Siu-tung had been perfecting for years, but it’s also idealistic: presenting Wong as a symbol not just of Southern China, but as a hero for the nation as a whole. Similarly, in allowing Western influences into his circle, going so far as to end the film wearing a Western suit and hat, Tsui’s Wong reconfigures the conflicts of imperialism, turning a political attack against Western (specifically American) racism and aggression into a moral tale of justice and righteousness, where color and national origin are deemed irrelevant in favor of the content of one’s character. That this is coded as a specifically mythical vision, with its fairy tale title and stirring theme song, opening and closing with a horde of men performing in unison on a beach at sunset, along with our knowledge of the way history would in fact play out (and which we’ll see over the next several films in the series), gives the film an air of tragedy. But the dream of integration remains a potent one.

Once Upon a Time in China II (Tsui Hark, 1992)

“When we are young, we learn the myths. And we interpret them as we get older. After all, we see they are just myths.” — Lu Haodong

“Gods are useless. You must rely on yourself.” — Wong Fei-hung

“Vigorous when facing the beatings of ten thousand heavy waves

Ardent just like the rays of the red sun

Having courage like forged iron and bones as hard as refined steel

Having lofty aspirations and excellent foresight

I worked extremely hard, aspiring to be a strong and courageous man

In order to become a hero, One should strive to become stronger everyday

An ardent man shines brighter than the sun

Allowing the sky and sea to amass energy for me

To split heaven and part the earth, to fight for my aspirations

Watching the stature and grandeur of jade-coloured waves

at the same time watching the vast jade-coloured sky, let our noble spirit soar

I am a man and I must strive to strengthen myself.

Walking in firm steps and standing upright let us all aspire to be a pillar of the society, and to be a hero

Using our hundredfold warmth, to bring forth a thousandfold brilliance

Be a hero

Being ardent and with strong courage

Shine brighter than the sun” — “A Man Should Strengthen Himself”

In some quarters seen as superior to the first film, perhaps because of its tighter focus (only a few main characters, including a recognizable-to-the-West historical figure in Sun Yat-sen), specific historical moment (set in September 1895 in the run-up to the Boxer Rebellion, as opposed to the vague late-19th century setting of the first film), and the presence of Donnie Yen (his second attempt at stardom, after supporting roles in a handful of films in the late 80s). I appreciate the grander sprawl of the first film, however.

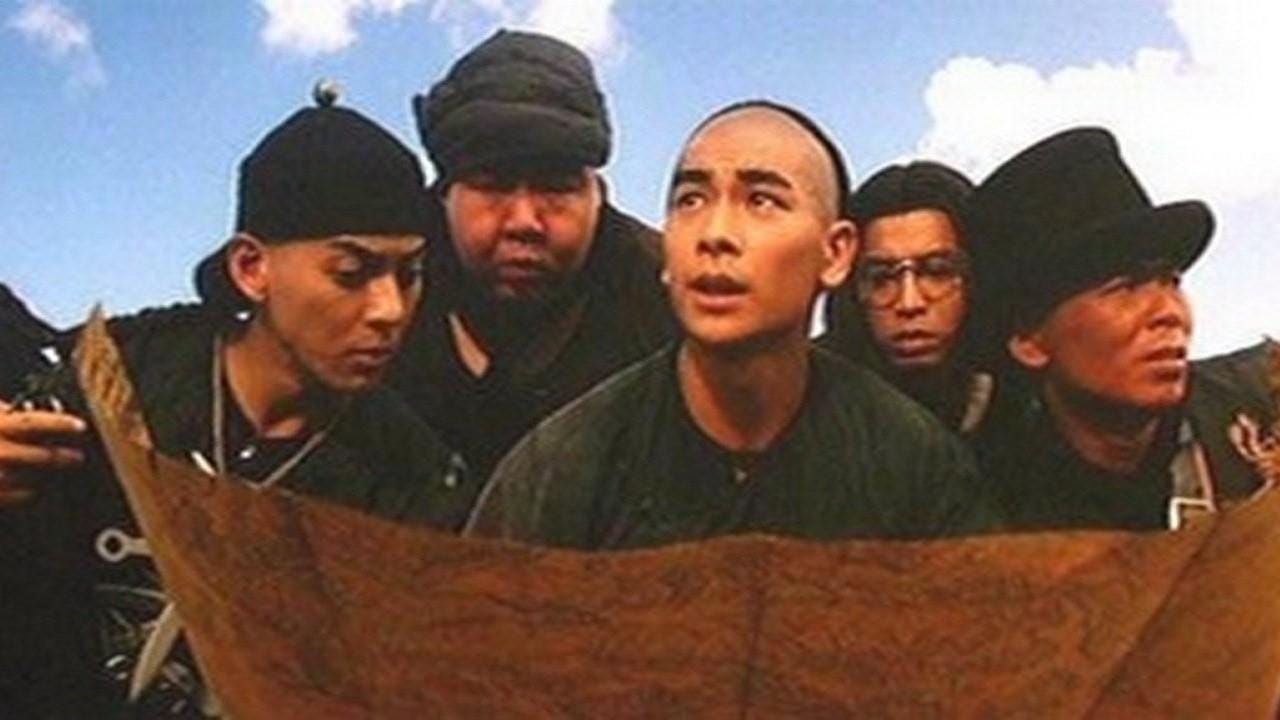

Wong Fei-hung, accompanied by Aunt 13 and Leung Foon (now played by Max Mok, who will play the role in the next four films in the series), travel by train to Canton, on the Pearl River Delta, 15 miles northeast of Foshan, for a medical conference. At the same time, the White Lotus sect is launching their branch of the Boxer movement, which in 1899 will flourish in the Rebellion in which fanatical anti-Western gangs attacked embassies and businesses throughout China, reportedly spurred on by the belief that their kung fu could stop bullets (see also Chang Cheh’s The Boxer Rebellion and Lau Kar-leung’s Legendary Weapons of China and The Spiritual Boxer). Aunt 13, wearing her Western dress and attempting to photograph a group of Boxers marching in protest of the Treaty of Shimonoskei, becomes a target of the gang. And when Wong’s conference is attacked as well, the three heroes attempt to make a quick exit out of town, but are delayed by the need to save a bunch of children.

At the medical conference, Wong meets and befriends Sun Yat-sen, who, as the head of the Revive China Society, is about to launch a rebellion against the Qing government, with the help of his top aide, Lu Haodong, played by 1970s Shaw Brothers star David Chiang. Sun and Lu are being hunted by the local Manchu commander (Donnie Yen), and in helping them, Wong becomes a target of the authorities as well.

So, once again, Tsui’s Wong becomes the center point of competing forces attempting to transform China: the Boxers clinging desperately to tradition; the Manchu clinging desperately to authoritarian power; the Republicans, trying to establish a Western-style democracy. But unlike in the first film, Wong doesn’t absorb and reconcile the contradictions, rather he chooses a side and fights against the regressive forces. He angrily confronts the Boxers in their temple, mocking their religious belief and exposing their leader as a sham. He helps Lu sneak back into Manchu controlled territory to destroy a list of rebels (which is based in historical fact: Lu was captured by the Qing in the process of destroying his roster, he was executed some weeks later), defeats Donnie and brings Sun the “Blue Sky with a White Sun” flag Lu had designed, which will become the flag of Sun’s party, the Kuomintang.

This isn’t Wong the integrationist, attempting to unify the nation through the sheer power of his moral example. He takes a side in this fight and the choice isn’t between whether to rebel or not, but in which way. Donnie’s commander initially seems OK, but is ultimately revealed to be purely evil, and with the Boxer leader given nothing to do but be exposed as a fraud, there is no counterweight to Wong’s sense of moral superiority like the one the tragic story of Iron-Vest Yim provided in the first film. Instead, the sequel’s villains are variations on the first’s purely evil Americans: men of violence and greed. With the decked stacked in this way, Wong can’t help but side with Lu and the kindly and just Dr. Sun, who go to great lengths to save lives but never take any themselves. This makes for stirring propaganda, and is a defiantly provocative move for Tsui, celebrating Sun’s Republicanism three years after Tiananmen Square and five years before the Handover. This version of a robust yet pluralistic China is bookended by armies of men (always and only men) strengthening themselves on the beach in a blood-orange dawn. The first time, it’s the dream of Wong Fei-hung, daydreaming out the train window and immediately follows a Boxer ritual prologue. The second time, it follows Sun’s unveiling of the KMT flag: Wong’s dream made real. Perhaps.

Once Upon a Time in China III — January 18, 2017

A major step down from the first two films in the series, really this is Tsui going through the motions, I wonder why he didn’t just farm it out to one of his Film Workshop underlings. Wong Fei-hung, Aunt 13, and Leung Foon visit Beijing, supposedly to inspect Wong’s father’s new steam-powered medicine generator (no explanation for why Wong Kei-ying, one of the famed "Ten Tigers of Kwangtung" is now a goofy old man living in the Manchu capital). While there, they get mixed up in an ill-conceived Lion Dance competition (sponsored by the Empress Dowager and the Prime Minister), which is being terrorized by a local oil tycoon. Also Fei-hung and Aunt 13 keep trying and failing to tell his father that they’re in love, while a pony-tailed Russian guy keeps hitting on Aunt 13, gives her a movie camera, and also is plotting to assassinate the Prime Minister because he’s secretly a Japanese agent.

It doesn’t make a whole lot of sense, but even the laziest of Tsui’s films have their moments of beauty. Were this simply an entry in a serial, it’d be totally fine, but as the third part of a trilogy in which the first two are stone-cold masterpieces, it’s a major disappointment.

“We can’t always hold on to things that are outdated.”

“I believe that history will change your point of view. But you’ll never see it.”

Once Upon a Time in China IV — February 12, 2017

Yuen Bun takes over for Tsui Hark, Vincent Zhao takes over for Jet Li, and Rosamund Kwan’s Aunt 13 is replaced by her sister Aunt 14, played by Jean Wang. Otherwise, this picks up right where the last one left off, with Wong hanging out at his dad’s place in Beijing to do some lion dancing. The plot mostly rehashes the last one, albeit with most of the complications of story and theme stripped away, impressive given that the last film was already a watered-down version of the first two in the series. In fact, with every iteration, Wong Fei-hung’s world becomes smaller, the issues confronting him less morally complex. Here the eight foreign nations occupying parts of the capital challenge the locals to a lion dance, which they use as an excuse to slaughter the Chinese with devious machinery, from hidden knives and gases to machine guns. The Germans lead the way, going so far as to hire a pair of Chinese mercenaries (Billy Chow and Chin Kar-lok) to carry out their killings. The time is 1900, in the midst of the Boxer Rebellion, represented here by a gang of fanatical women who go around killing foreigners, a total replay of the cult of Boxers in the second film, except being female they’re somewhat more sympathetic (one of them even falls for Wong).

The action is merely mediocre, Yuen working within Tsui’s quick cutting style, but Zhao doesn’t have Jet Li’s grace. In the first films, the action is more rhythmic: long takes of Li’s remarkable athleticism giving weight to the impressionist cuts of impossible feats. But Zhao can’t sustain his fights as long as Li can, which throws the rhythm off: everything is too quick and feels phony. Yuen compensates for the more limited abilities of his performers in his extensive work as choreographer for Johnnie To by incorporating long passages of stillness in between the action movements, with sharp geometric arrangements of characters and objects building suspense. Tsui will go the opposite direction with Zhao in The Blade, cutting everything to shreds in creating an impressionistic blur of wild violence. But while the stunt-work and choreography in Once Upon a Time in China IV are totally fine, and Zhao, Max Mok, and Hung Yan-yan (again playing Wong’s companions Leung Foon and Clubfoot) are totally capable performers, the most interesting things in the fights are the lion props, especially the cute and terrifyingly clever monsters the foreigners have prepared, taking a Chinese tradition and bastardizing it into something brutal and murderous.

The tone darkens considerably at the end, with a blood-red sunset and word coming that while Wong and his men labored to win the symbolic lion dance contest, the foreigners were busy forcing the capitulation of the Empress Dowager in the Forbidden City. Wong and his family and friends pack up and head for home.

Once Upon a Time in China V — February 14, 2017

Tsui Hark is back as director, and Rosamund Kwan returns, but Jet Li is still missing. The story picks up where the last one left off, with Wong Fei-hung and his family and friends heading south after the failure of the Boxer Rebellion. They meet up with Aunt 13 and Porky Lam (Kent Chang is back for the first time since the first film) and get waylaid by pirates before they can flee to Hong Kong.

It’s unclear what city the action takes place in: it seems like 13 and Porky are waiting for them in Foshan, but they don’t seem to know anyone else in town. Probably they met somewhere along the way to catch the boat for the colony. Anyway, most of the film is Wong Fei-hung fighting pirates, by which I mean it’s pretty cool: the best action since the second film (Tsui in particular has a lot of fun integrating guns into the action; who knew Buck-Toothed So was an ambidextrous crack-shot?). The blackest and goriest film in the series, it’s a transitional film on the way to the next year’s The Blade.

As government troops finally arrive to take charge of the situation, in two separate groups with contradictory orders, the town’s rice monopolist recites the epitaph:

“The more unstable the society, the more opportunity for profit. All the prices go up and there are fortunes to be made. Heroes appear in troubled times. That’s the time to strike it rich. Prosperity has gone up in smoke. There’s nothing left.”

Once Upon a Time in China and America (Sammo Hung, 1997)

I will never not think it’s hilarious that Sammo Hung and Tsui Hark stole Jackie Chan’s dream project idea for a kung fu Western and used it to make a sixth Once Upon a Time in China movie. I bet he’s still mad about it. I haven’t seen Shanghai Noon, but I have no doubt it’s glossier, better acted, and much much worse than this. That this was the last project for both Sammo and Tsui before they too arrived in America is surely no accident. For a long time I thought Jackie got his revenge by both ripping off the concept of Sammo’s TV series Martial Law for Rush Hour and also by making a ton of money. But it turns out Sammo only added Arsenio Hall to his show after the success of Rush Hour, so he was just ripping Jackie off again. But Sammo never had to work with Brett Ratner.

Totally abandoning any kind of logical chronology, Wong Fei-hung (with Jet Li returning in the role), 13th Aunt, and Clubfoot (now named “Seven”) are in America to visit Buck-Toothed So, who has opened an American branch of Po Chi Lam for Chinese workers in Fort Stockton, which might be a made up place, though there is a Fort Stockton in West Texas, I suspect it would take more than ten days to get there by stagecoach from San Francisco by OUATIC travel time (where it takes three days to get from Hong Kong to Guangzhou (it takes two hours today). The last film ended after the Boxer Rebellion failed, which would mean this one would take place more than a year after that (So was still in China in that film), so at least 1903. But the Fort Stockton we find is a relic from 30 to 40 years earlier, if for no other reason than that the Chinese Exclusion Act, barring immigration from China, was passed in 1882.

It’s clear that Wong hasn’t so much journeyed to America, as he’s journeyed into a Western. The characters and setting aren’t historical, they’re versions of cinematic history. It’s not real Native Americans he finds, but movie Indians: first attacking a stagecoach for no reason, then adopting the amnesiac Wong into their peace-loving tribe, Pocahontas-style. Throwing Wong Fei-hung into a Western completely destabilizes it, his moral vision reforming Billy the Kid into an upright pillar of the community, while his speeches do little for his own community, putting the laborers, led by Richard Ng and Patrick Lung Kong, to sleep. The villains in the film are the racist white establishment, led by the corrupt mayor. Local law enforcement (the kindly sheriff) is sympathetic yet powerless in the face of greed and anti-Chinese sentiment. That the film’s final villain (a bank robber hired by the mayor) is ethnically ambiguous, sporting Fu Manchu eyebrows and beard and deadly ninja star spurs, is surely no accident: what Wong conquers is not so much racism as a version of Hollywood racism, the Yellow Peril monster of America’s id.

The final fight is striking: seven Chinese men set up to be legally lynched, incidentally rescued by the betrayed criminal gang in their quest for revenge on the mayor. Wong and his men defeat the villains of course. But after the fight is over: 13th Aunt arrives with the friendly Indians who had adopted Wong: a cavalry appearance too late to save anyone, but a nice gesture nonetheless. Wong though, refuses to recognize them: even Wong Fei-hung forgets the Indians.