Linda Linda Linda (Yamashita Nobuhiro, 2005)

Yesterday was the first day of school for my kids, which I would suggest should be a national holiday for stay-at-home parents, but then, there wouldn’t be school on a national holiday and that would defeat the purpose. I celebrated in the usual way: watching Linda Linda Linda, a perfect movie which is maybe the most joyous film I know. It’s a movie about four high school girls who throw together a band to learn three songs in three days to perform at their school’s festival. The songs are by the pop-punk band The Blue Hearts, the first of which, with the addition of a third “Linda,” gives the movie its title. The film has been newly restored and, thanks to GKIDS, is opening in theatres this weekend in New York and LA before rolling around to art houses around the country over the next few months.

Linda Linda Linda is part of a glorious tradition of rock n’ roll movies, dating from the start of it all with attempts to fit the new musical idiom into the Hollywood tradition in movies like The Girl Can’t Help It, Bye Bye Birdie, and the films of The Beatles and Elvis Presley, through the jukebox innovations of the 70s in American Graffiti and Rock ’n’ Roll High School on through John Waters’s 80s rock movies. The pre-rock DNA can be traced all the way back to the “putting on a show” musical revues of the 1930s as well as the musician biopics of the 40s. The more immediate precursor is Obayashi Nobuhiko’s The Rocking Horsemen, which is also about high schoolers forming a band. What distinguishes Linda Linda Linda, from these predecessors (not to say it’s unique or the first to do any of these things) is its compressed time scale, its centering young women, and its realism. Linda Linda Linda is the rock ’n’ roll performance musical in the style of slice-of-life anime, a formula repeated in the masterful Kyoto Animation series K-On!! and Sound! Euphonium (both directed or supervised (I guess? anime credits are weird) by Yamada Naoko, who also directed the film extensions of the two series), shows which combine everyday teen melodrama with light, at times absurdist, humor and a genuine love of making and performing music with other people (Yuasa Masaaki’s Science Saru series Keep Your Hands Off Eizouken! does something similar, albeit with filmmaking instead of music).

The time scale creates a kind of ticking clock scenario, where the girls (Bae Doona as Son on vocals, Maeda Aki as Kyoko on drums, Kashii Yuu as Kei on guitar, and Sekine Shiori as Nozomi on bass) have to rush to learn their songs, compounded by the fact that at least half of them don’t really know what they’re doing: Kei is normally a keyboardist who doesn’t know guitar very well, and Son, chosen at random to be the singer, is a Korean exchange student whose Japanese is not very good at all. Thus they have to practice essentially every waking minute of the next few days, and quite a few of the non-waking minutes too. Of the actresses, only Sekine was an experienced musician, being the bassist for the band Base Ball Bear (they appear in a couple of songs on the film’s soundtrack). The actors’ amateurism thus matches that of the characters, and is of course perfect for playing punk rock. When they first start, they’re terrible. But as they work, they get better, and we see their incremental improvement over the course of the film, culminating in the three climactic performances. Crucial to what makes the film work is that gradual process. Things don’t just suddenly click for them: they work and work and work and their development never seems like movie wish-casting, but the actual product of artistic labor.

The setting among high school girls is somewhat unique as well. Obayashi’s film followed a rock-mad boy, but other rock movies centered women, though usually as fans (Ann-Margaret in Bye Bye Birdie for example, or PJ Soles’s iconic Ramones fan in Rock ’n’ Roll High School). I’ve got a theory that one of the reasons Linda Linda Linda and other slice of life films and series (Iwai Shunji’s April Story and Hana and Alice films, for example) resonate so strongly with me, and indeed more so the older I get, is because their world is so alien to my own. There’s very little in common between my high school experience as a teen boy in Spokane (let alone my present as a middle-aged parent) and the experiences of musically-inclined Japanese girls. But that distance is what makes empathizing with these characters so powerful: I have to make an imaginative leap to try to understand their world and their concerns, which means I invest a little bit of myself in the film. This is how melodrama is supposed to work, of course, but mainstream film and television seems to have lost interest in trusting the audience to bridge those gaps in the name of identification. Maybe this is why my kids, who are music playing teens and thus demographically positioned (though American rather than Japanese or Korean) to identify strongly with the characters in Linda Linda Linda, simply aren’t as impressed with the movie as I am. Or maybe they’re just wrong.

Director Yamashita Nobuhiro though understands the way that distance paradoxically creates understanding, and he uses multiple effects to keep us separated from the main characters. The crisis that necessitates the reconfiguring of the band is introduced in the movie’s opening moments, before we know who any of these people are, and always obliquely. We know that someone got injured, and someone else quit the band, but we don’t really know why and we never will. Similarly, the girls’ high school is filled out with more than a dozen other characters, each of whom are fully individualized through actions, gestures, and looks (and never, thank God, flashbacks or expositional dialogue), despite their limited screen time. There’s the AV kids trying to make a documentary about the festival; the kids who volunteer to run the thing, presumably as corporate management training; the teacher who seems totally uninterested but isn’t actually; the poor guy who tries to tell Son he loves her in Korean, to her great confusion; the girl who broke her finger who sings a lovely Joan Baez-esque version of the folk standard “The Water is Wide”; the coolest girl in the school who hangs out on the roof drinking whiskey and reading comics who rasps like Natasha Lyonne and is a masterful guitar player; Kei’s ex-boyfriend who has access to a studio and is otherwise just sleeping in his car in the middle of the day; and on and on. All these people have a life outside the movie, and by not bothering to tell us about it, Yamashita allows us to feel like we’ve merely caught a glimpse of a fully-realized world.

This approach extends to the way he films the performances. Obayashi centered his film closely on the sound and the look of an electric guitar and amplifier playing the opening notes of the great Shawnee guitarist Link Wray’s classic “Rumble.” Yamada too, in her series and films, emphasizes close-ups of the instruments and performers, an approach she extends to the series as a whole in Sound! Euphonium and its off-shoot, Liz and the Blue Bird, where the image repeatedly cuts away from standard framing to follow the swish of a pony tail, or a student’s feet, or their fingers as they play their instrument. Yamashita though pulls us away from the instruments to take in the band as a whole. This is more egalitarian of course, in that it emphasizes how much the film is about their learning to play together, not just to play, and it doesn’t privilege one actor over another.

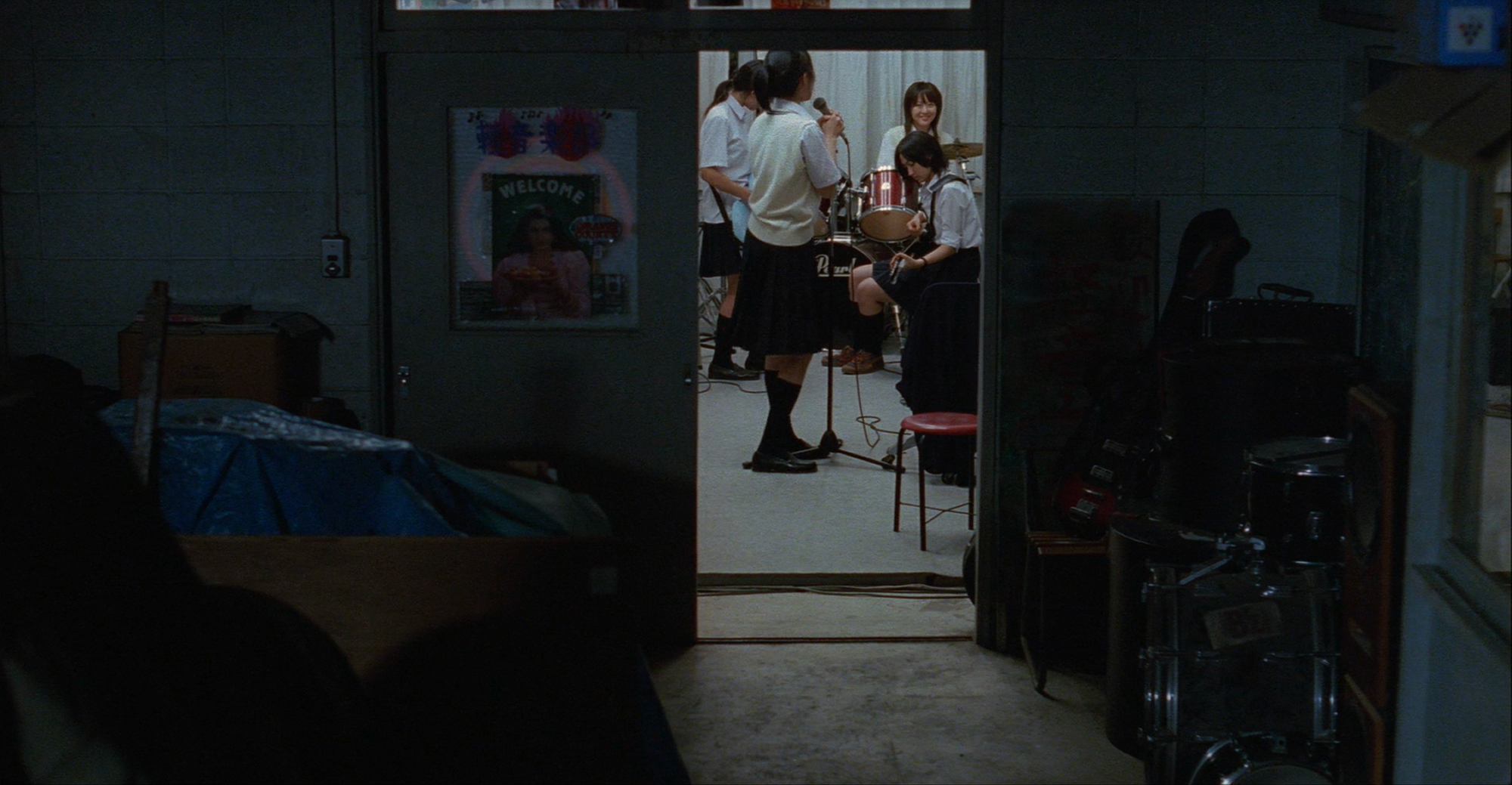

Maeda and Bae were the only real name actors at the time of filming, with Maeda surviving Fukasaku Kenji’s Battle Royale and Bae opening her career with a killer trio of Bong Joon-ho’s Barking Dogs Never Bite, Jeong Jae-eun’s Take Care of My Cat, and Park Chan-wook’s Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance. But Kashii gets the movie star part, as the diving force of both the band and the narrative, and Sekine’s presence anchors both the band and the film in real-world competence (like a bass should). In any rock band, of course, the singer will tend to be the primary focus of the audience, but Yamashita works against that by not centering Bae’s singing in the image. In the first climactic number, for example, a rehearsal of “Boku no Migite”, Yamashita films in a continuous take, with the camera positioned in the hallway outside the rehearsal room. We see the band through a doorway, with blank space filling up more than half the screen. Bae is facing off to the right as she sings, and we understand her and the band’s increasing confidence and groove as she begins to bop in time to the now-tight rhythm section. Similarly, in the film’s concert climax, Yamashita films the band head on from a distance (which shows the audience in the foreground, not exactly sparse but that really only because of the driving rainstorm outside), but Bae mostly in profile as she belts out the film’s title song. Withholding the traditional identifiers of stardom, Yamashita draws us ever further into the characters and the music. The result is overwhelming, an explosion of musical joy unprecedented in film history.