Jeffrey Lau Capsule Reviews

The Haunted Cop Shop (1987) — July 25, 2020

Jeffrey Lau-directed and Wong Kar-wai-written mash-up/parody of the Chinese vampire and girls with guns genres. The vampires are more Western though (with a backstory about the Japanese occupation to satisfy the critics) and the GWG stuff is mostly just Jacky Cheung and Ricky Hui harassing Kitty Chan. She only made a couple more movies after this, the last being Haunted Cop Shop 2. It’s not hard to see why.

I suppose it’s a kind of missing link between classic Hui Brothers comedy (with Cheung in the Sam role and a Michael figure sorely missing) and the later, much better Jeffrey Lau stuff. Maybe he needed Stephen Chow to set him on the right track.

All for the Winner (1990) — December 25, 2013

The thing about these Hong Kong gambling movies is that they’re sports movies, but they’re not about making yourself a better person or coming to terms with your past or personal redemption or any of those things American sports movies are about. They’re about perfecting your skill such that you can get away with cheating. They’re the manifestation of free-wheeling Hong Kong capitalism in the last days before the Handover to China. A last gasp of anarchy before the fall. It’s a world where everyone is cheating, everything is a hustle, and the naive hero (a bumpkin from the mainland city of Guangzhou (population 6.3 million in 1990, more than twice that today) must learn how to cheat consistently and effectively to get ahead.

He’s also lectured near the end by co-director Corey Yuen that he should use his superpowers to help the poor. And maybe he will. But even then it’ll be the philanthropic largesse of the robber barons, the laissez-faire capitalists that cheated their way to the top then built libraries and universities and museums with their spare change. Social goods all, does it really matter where they came from?

Also, Ng Man-tat begins convulsing and starts humping everything in sight whenever Stephen Chow says his name.

The Eagle-Shooting Heroes (1993) — August 5, 2019

There’s just something so lovable, so pure about the Hong Kong tradition of making the sexiest, coolest people in the world act like complete idiots for a hundred minutes.

A Chinese Odyssey (1995) — April 3, 2018

This is I think the third time I’ve seen this, but the first two were years ago. I figured I’d have a better handle on it now, having seen so many Journey to the West and Monkey King movies in the intervening years, and I’ve even read some of the book itself.

I was wrong.

Somewhere near the end, I managed to figure out what was going on, and not only that, I caught an inkling of why it was all happening. In this sense, the two films, with their impossible plotting and maddening tangle of relationships made all the more inexplicable thanks to a fungibility of identity, mirror the spiritual condition of humanity. We’re all too dizzy to understand anything, let alone actually achieve some kind of peace or enlightenment.

I think Stephen Chow captured the philosophical nature of the quest more successfully in his Journey to the West movie, but no maker of wuxia farce was more elaborate, and more dedicated to parodying Ashes of Time and Chungking Express, than Jeffrey Lau in the mid-90s.

Added August 12, 2019:

One thing I couldn’t quite figure out how to cover when I wrote about this at The Notebook was that while the Chinese Odyssey films are the end-point of the mo le tau genre, they’re also one of two endings for the high-speed comic wuxia subgenre of the early 90s (the Swordsmans and Fong Sai-yuks and Kung Fu Cult Masters). The other is Tsui Hark’s The Blade, also released in 1995. The one emphasizes the genre’s bright and goofy side, the other its worlds of unrelenting violence.

Chinese Odyssey 2002 (2002) — April 24, 2014

Bears no real relation to A Chinese Odyssey, director Jeffrey Lau’s epic Journey to the West tale starring Stephen Chow. But it does capture that spirit of early 90s Hong Kong comedy: a period-set romance with lots gender reversals and a whole lot of Wong Kar-wai parody. Faye Wong is the princess who runs away from the palace and disguises herself as a man. She meets Tony Leung, the local tough guy (his name is “Bully the Kid”) and his sister, played by Zhao Wei, a tomboy who everyone in town is afraid to date because her brother is so terrifying. Faye and Tony become instant best friends and he tries to get her to marry his sister, though she is really in love with him and him with her. Faye and Tony sing a duet as they eat and drink a lot. Then Faye leaves to go home and Chang Chen, the young Emperor, shows up looking for her, disguised as an actor. He falls for Zhao, who appreciates him not for his disguised wealth, but seems to generally like his ideas for modernizing the empire, like shaking hands as a greeting instead of bowing, and platform shoes and giant Afros. Zhao wants to marry Chang but can’t because she feels obliged to Faye who actually loves Tony who is very confused.

All of this, told with a narrator, an overblown Wongian voiceover, and cutaways to direct address interviews, and scenes replayed Rashomon-style as excerpts from the various characters’ memoirs, is hilarious enough. But in the final third, Lau pulls the neatest twist of all and turns this ridiculous story into a genuinely heartfelt and moving, even sweet, romance. How did that happen?

A Chinese Odyssey Part III (2016) — February 25, 2017

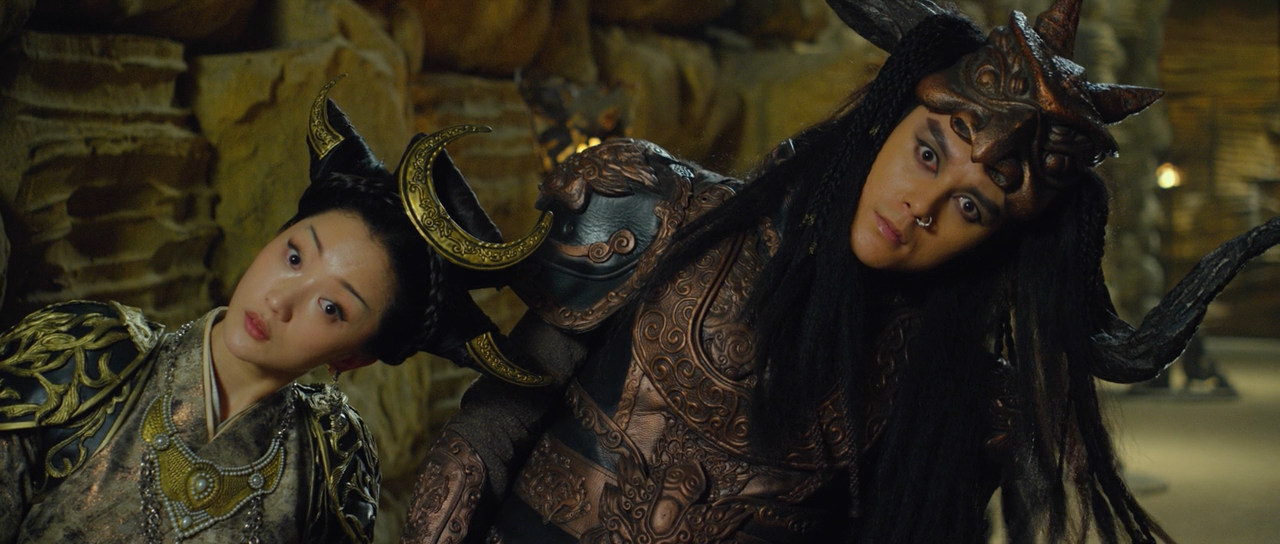

If any director deserves the “visionary” label, it’s Jeffrey Lau. A reshuffling of the Journey to the West story, where Tiffany Tang, as the twins Zixia and Qingxia uses the time-travel device Box of Moonlight to glimpse the future, where she sees herself die to redeem the Monkey King. To save herself she tries to manipulate the future, inadvertently uncovering the Jade Emperor’s scheming to cover up a mistake in the Sealed Book (the repository of fate and destiny). With her trying to change the future and his trying to change the past, everything gets crazy and causes chaos in the lives and romances of the Demon Bull King, his sister White Snake, his wife Princess Iron Fan, Joker (who because of the mistake in the book won’t become the Monkey King for 500 years), the Longevity Monk (Xuangzang, who has been time-traveling himself and makes his first appearance dressed as Smooth Criminal Michael Jackson), and Six-Eared Monkey (enlisted by the Jade Emperor to impersonate the Monkey King).

It’s kind of related to the first two Chinese Odyssey films (Karen Mok briefly returns as Pak Jingjing), I think. But one of these is hard enough to follow, let alone three. It is, I’d guess, half a reboot and half a remix, with Zixia/Qingxia fooling around the with the fundamental premises of the 1995 version, while revealing the incompetence and manipulations of the all-powerful authority behind everything. There’s a message there about lunatics from Hong Kong gaining access to the resources of the Chinese marketplace sneaking critiques of the State into a whirlwind of flash and nonsense.

Regardless of whether the film’s plot makes sense (and I think it does, emotionally at least, though not as much as the 90s films and certainly not as much as Lau’s masterpiece, the unrelated A Chinese Odyssey 2002), it’s stunning to look at, from crazed cartoon CGI battles to gorgeous costumes and sets to simple, impossible landscapes (a purple sky bursting with fireworks is a particular favorite). The first two films had Stephen Chow as Joker/Monkey King, and mid-90s Chow was an incomparable special effect unto himself. None of the new film’s performers are close to that interesting, and even the best ones (Wu Jing, Tiffany Tang) don’t get much to do, as everything moves so fast they’re consumed by the spectacle. Chow’s own Journey to the West films are much more profound, while Soi Cheang’s occupy a kind of middle-ground, not too deep, not too confusing, not too beautiful.