Iwai Shunji Capsule Reviews

Fireworks, Should We See It from the Side or the Bottom? (1993) — November 7, 2018

Iwai Shunji, with no budget and only a couple of ideas, making all the other TV movies look terrible.

Love Letter (1995) — November 7, 2018

Maybe the most accomplished feature debut of his contemporaries, probably because Iwai had been making videos and TV movies for years leading up to it. The balance between storylines, past and present, city and country, linked via letters and Nakayama Miho playing a dual role, and generic modes, romantic comedy and tragedy, is so assured, so deftly done. The movie is lighter than air, leavening both the sweetness of young love and the bitter sadness of loss.

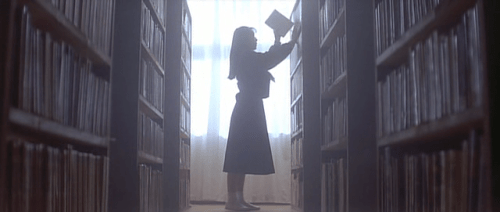

April Story (1998) — November 7, 2018

I’ve adored this film for years and so rewatched it with some degree of trepidation.

But nope, it’s still pretty much perfect. Maybe the best movie about shyness. And cherry blossoms. And looking for an umbrella. And fly fishing.

All About Lily Chou-chou (2001) — November 8, 2018

I said this before, but this is the A Brighter Summer Day for the message board era. But Iwai lacks Yang’s precision. His propensity for dreaminess, in soundtrack and editing, undercuts the impact of the film’s social critique. It’s a mood of alienation, rather than a portrait of it. That’s not invaluable.

We float in Iwai’s other teen dramas. In this one, we drown.

Hana and Alice (2004) — November 7, 2018

I haven’t seen all of Iwai Shunji’s films, or even most of them, but the ones I have seen all circle around middle school, and young adulthood, and the various trials, mostly romantic, thereof. Of these, Hana and Alice is probably the most complete encapsulation of his approach, of his obsession with doubling and memory and the written word. It has a lightness that’s missing from All About Lily Chou-Chou, which for all its brilliance feels like Iwai is attempting an Edward Yang imitation. Hana and Alice is him doing his own thing, and is vastly freer, and fresher, for it.

But I am a sucker for the ballet.

A Bride for Rip Van Winkle (2016) — May 25, 2016

If All About Lily Chou-Chou was the A Brighter Summer Day of the message board era, then A Bride for Rip Van Winkle is the Mahjong (Or Yi yi?) of the age of social media. A sprawling three hour epic of loneliness, Kuroki Haru stars as Nanami, a young woman adrift in a world where the virtuality of identity has spread from the internet to pervade every aspect of life. Not in a sci-fi sense à la the dystopic Her, but in the blithe mutability of everyone she meets. She finds her fiancé online, but never really gets to know him. For her wedding, not only do her divorced parents pretend to still be a couple for the groom’s family, but she hires actors to fill out her side of the aisle (she’s totally disconnected from her extended family). For this task she elicits the help of a mysterious young man who makes his living in fakery: actor, private detective, agent, hustler, creator. He’s a facilitating figure, leading Nanami ever further into a labyrinth of abstraction.

But here’s the twist: as Nanami becomes increasingly alienated from everything we understand to be “real” (family, career, personal history), she becomes proportionally more invested emotionally in her phony world. The woman so quiet and reserved that her students gave her a microphone so that they could hear her speak finds herself the center of a romantic tragedy of operatic proportions. The old relationships based in traditional structures dissolve in the mediated world, which can be isolating and cruel, but within that media lies the potential for new forms of connection, which can perversely be all the more intense for their artificiality. This isn’t an especially revolutionary insight, but the patience with which Iwai accumulates the details of Nanami’s life and perspective, the determination to confound our expectations of what the narrative is and where it is headed, turn what could have been a movie-as-hot-take into a sneakily complex emotional experience. In other words, a first-rate movie melodrama.

Chang-ok’s Letter (2017) — February 27, 2017

Doona Bae drives a PT Cruiser.

The 12 Day Tale of the Monster that Died in 8 (2021) — August 9, 2021

Iwai Shunji is one of the most reliably adventurous mainstream directors in world cinema today. A quick look at his recent output: after his epic 2015 chronicle of a lonely woman and the internet (A Bride for Rip Van Winkle), he made an animated prequel to one of his best films (The Case of Hana & Alice), an hour-long movie about Bae Doona as an alienated housewife that was actually an extended commercial for Nescafé (Chang Ok’s Letter), and two versions of the same film made back to back, one in China and one in Japan (Last Letter). So it shouldn’t come as any surprise that his latest is an adaptation of a COVID-boredom challenge by Shin Godzilla co-director Higuchi Shinji, wherein a variety of celebrities would make short films about their kaiju defeating COVID called, naturally, “Kaiju Defeat COVID”.

Saitoh Takumi (star of the upcoming Shin Ultraman) buys a kaiju egg online and talks about it with us in videos and with his friends in zoom chats. One of the friends is a director who is a kaiju expert, another is a chef who is out of work thanks to the shutdown, the third is played by Non (star of Ohku Akiko’s Hold Me Back), who purchases her own creature online, an alien that can’t be seen on video. The kaiju are tiny, starting as pea-sized balls but taking on various forms as the days go by and they evolve. Takumi is continually perplexed by what his kaiju is and what its final form will be. Is it a Windom? A Miclas? A Ballonga? A Devilman? Will it, as he hopes, defeat COVID, or will it destroy the world (if it does, he tells us, he will truly be sorry)? There are a couple of interesting ideas here: the matter of factness of a world where every popular Japanese genre cycle reflects an actual reality (successive waves of kaiju, aliens, ghosts, etc, our inability to understand “what COVID means”, and our powerlessness in the face of it, along with the widespread false belief that the cure might be worse than the virus itself.

The isolation and desperation of the shutdown are palpable in the videos, creative people slowly losing their minds from lack of social contact. It’s also a lightly funny parody of YouTuber culture, the kinds of videos my kids watch that don’t make any sense to me (Takumi is particularly fond of a woman who live streams from her bathtub (fully clothed and with no water, of course). At times, the film veers dangerously close to cuteness, often a danger with Iwai, but as with his 1998 film April Story, which I think is his best work but which some find overly saccharine, he grounds it with just enough melancholy and deadpan weirdness to avoid that adorable fate.