Crosscurrent (Yang Chao, 2016)

Poetry is the subject of the moment for 2016. Like Volcanos and Asteroids and Mars before it, we’ve been blessed this year with a plethora of films about writers of verse. Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson, Terence Davies’s A Quiet Passion, and Pablo Larraín’s Neruda have all the headlines, and as great as those are (and the first two are without a doubt, great films, while the third, well, isn’t really about poetry and I’m not sure how much it’s about its poet either), the best film about Poetry here at VIFF might just be Yang Chao’s Crosscurrent. Like last year’s Kaili Blues and VIFF 2013’s Four Ways to Die in My Hometown, it’s an independent, somewhat obscure Chinese film where the lines between past and present, myth and reality, documentary and fiction, are difficult to grasp.

Reversing the direction of Jean Vigo’s great river film L’Atalante, Yang follows a boat on its journey up the Yangtze from Shanghai to its source high on the Tibetan plateau. The captain, whose father has recently died, sees a woman in the Shanghai harbor but fails to meet her. The next night, the boat’s engine stops working and the captain finds, hidden in the machinery, an old and dusty book, filled with poems chronicling another man’s journey on the river (dated 1989), a different poem for every stop on the way along the third longest river in the world. The engine restarts (for machines always work better when you take the poetry out of them) and the journey begins in earnest.

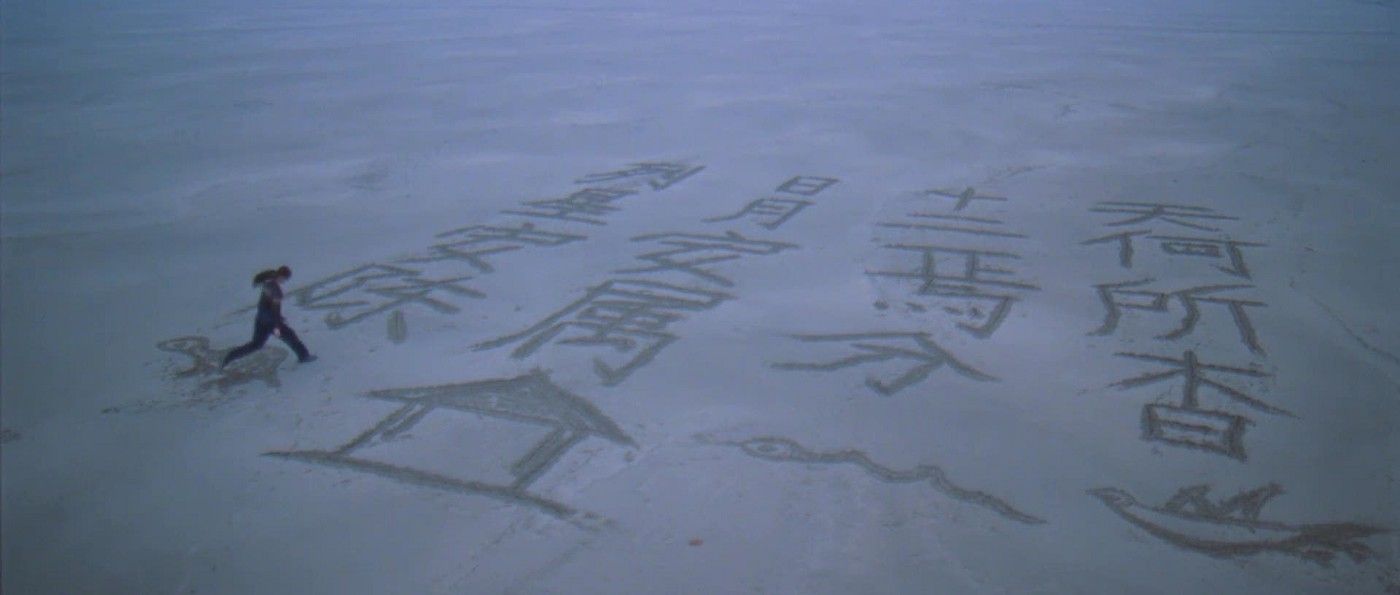

On-screen titles give us the locations of each stop, along with how many days the boat has been running, as well as the corresponding poem, composed by Yang himself. At each stop, the captain sees the woman again, always looking for him on the shore. They fall in love, have sex, make food, steal vegetables, but always he goes back to his boat and always she reappears further down the line on land.

Ace DP Mark Lee Ping-bing shot the film on 35mm: back in 2012 (when it was filmed) digital technology was incapable of capturing his desired images: the fog and steam of the harbors, the depths of night on the river (a beam of light tracing the movements of the woman high on a cliff-face), the pairing of the woman’s face, in close-up with a ball of fire: first a lamp, then a candle flame (the floating balls of light Lee found in Hou Hsiao-hsien’s The Assassin appear briefly here as well). Two-thirds of the way up the river, the Three Gorges Dam severs their connection, its locks taking over the movement of the boat with a ear-shattering, inhumane shriek, throwing the vehicle out into an artificial landscape, through the drowned villages of Still Life and past towering limestone cliffs. The Dam is the definitive break with nature, with the past: modernity cannot recapture what went before, and the captain and the woman can no longer meet. The central mystery of the film is ungraspable in all the best ways. The woman at times seems the soul of the river, or an apparition from the past, doomed to repeat her tragedy, Marienbad-style. She could be a manifestation of grief, of longing, of loneliness. She’s all of that and more, and the captain, lost in his dream, can only follow her to the river’s end.