Chung Mong-hong Capsule Reviews

The Fourth Portrait (2010) — October 6, 2010

This Taiwanese film is about a precocious young boy named Xiang whose father dies, sending him first into the helpful hands of the school janitor, and then back to his mom, a prostitute (naturally) and step-father (who’s pretty much pure evil). Director Chung Mong-hong keeps this dire material much lighter than one would expect. Though the kid’s situation is rough and potentially terrifying, there’s enough humor and visual style (there are traces of both the Taiwanese New Wave and Wong Kar-wai, the latter especially in the scenes at the mom’s “lounge”) that things never get as horribly depressing as they might in a lesser film. There’s even a musical bit that sounds like a Chinese version of the Carl Orff song used in Badlands and True Romance. Xiang is surrounded by helpful adults, from the elderly janitor to a small time hustler to a concerned teacher. Even his mom is a decent sort. We never get the sense that Xiang’s situation is hopeless, instead, we can be sure that he’ll survive and thrive. The title comes from a series of drawings Xiang makes throughout the film: the first is his father, the second his friend the hustler, the third his older brother who may be haunting him, and the fourth, more than a little cheesily, is the film itself.

Godspeed (2016) — July 11, 2017

Taiwanese director Chung Mong-hong’s Godspeed starts like any other gangster picture: a mysterious man is led by mysterious men to a red room in Thailand for a tense and bloody encounter. Then we see that same mysterious man in calmer times, discussing sofa maintenance with a crime boss. Then a young man is sent on a mission, he's apparently a killer for hire or some other kind of mob underling. All he needs is a ride, but the cab that picks him up is driven by Michael Hui. Hui is one of the great comedy directors and stars of the past 50 years. His series of hits in the 1970s and 80s helped revive the Cantonese language in cinema and form the missing link between the classical American comedy tradition to the nonsense films of Stephen Chow. He presence in this Taiwanese film alone is enough to destabilize it, and he does, playing one of his trademark characters, a sad sack cheapskate hustler. His oddball brings out the absurd in gang movie cliches, while the moody suspense and violence bring out the melancholy in Hui’s everyman struggles. The resulting film is too shifty to grasp, moody and ephemeral, grippingly bleak and cruel, yet sad and somehow weirdly hopeful.

The Falls (2021) — September 16, 2021

Chung Mong-hong is the kind of director who seems tailor-made for the international art house circuit but for some reason has yet to break through with American audiences. A regular on the festival scene, and a frequent recipient of awards at home in Taiwan (the Best Director Golden Horse for both his 2010 The Fourth Portrait and 2019’s A Sun, which also won Best Picture, alongside numerous other nominations for these and his films Soul (2013) and Godspeed (2017)), he’s an accomplished, precise, professional filmmaker, kind of a Taiwanese Koreeda Hirokazu. The Falls is his pandemic movie, the latest in a series of Chinese-language films about fraught parent child relationships along with Yang Lina’s Spring Tide, Yang Mingming’s Girls Always Happy, and Wang Chun’s Mad World among many others. Like the latter, the film complicates its central relationship with mental illness, in the case the mother, played by Alyssa Chia. She’s some kind of office worker at a multinational who has to leave work suddenly when her 17 year old (Gingle Wang) is sent home from school because one of her classmates tested positive for COVID (the name is never mentioned, but you know). Mother and daughter are forced to quarantine together, and the strain leads the mother to a psychotic break: paranoia, hallucinations, and eventually a small fire.

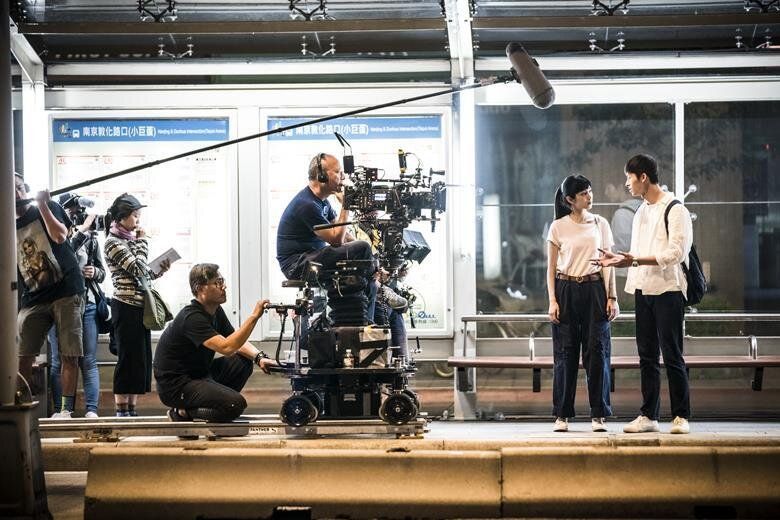

But that’s just the first half of the movie. While Chung carefully documents the woman’s breakdown, the gradual introduction of chaos into her meticulously appointed apartment (captured in all it’s sharp-edged crystalline clarity by Chung, working as usual as his own cinematographer, though this time not under his pseudonym “Nakashima Nagao”), he’s just as interested in the processes by which her daughter attempts to cope with the situation (loss of income from her mother’s lost job primary among them). It’s not just a film about how the pandemic broke us, but about our struggle to make things normal again after the flood. Bit by bit the women rebuild their lives and their relationships with each other and eventually the outside world. But then in the final minutes Chung, always just a little bit more perverse than he should be (perhaps this explains his lack of success in the US market), can’t help but undermine the feel-good ending his film seemed to be building towards. Because the thing is, even when the pandemic has passed, being a parent, and for that matter being a child, basically just being alive at all in the world with other people, is absolutely terrifying.