Angel's Egg and The Red Spectacles (Oshii Mamoru, 1985 & 1987)

Two restorations of Oshii classics are in theatres now

This week GKIDS is presenting the new restoration of Oshii Mamoru’s avant-garde 1985 anime Angel’s Egg in special engagements in theatres across North America. As part of the celebration, the Metrograph in New York City has programmed a special series on Oshii and his influences, which in addition to the restorations of Angel’s Egg and his 1987 live-action film The Red Spectacles, includes such influences as Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker, Luis Buñuel’s The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and Suzuki Seijun’s Branded to Kill. I’ve seen all of those films, but until this week I hadn’t seen either of these Oshiis. The only one of his movies I’d seen before, in fact, was his seminal 1995 anime Ghost in the Shell, which at the time I watched it (late 90s-early00s) was essential Intro to Anime material, along with Akira, Neon Genesis Evangelion, Ninja Scroll, and Cowboy Bebop. Having now watched them, I’d say the Metrograph series gives a pretty decent idea of what these two singular films taken together are like.

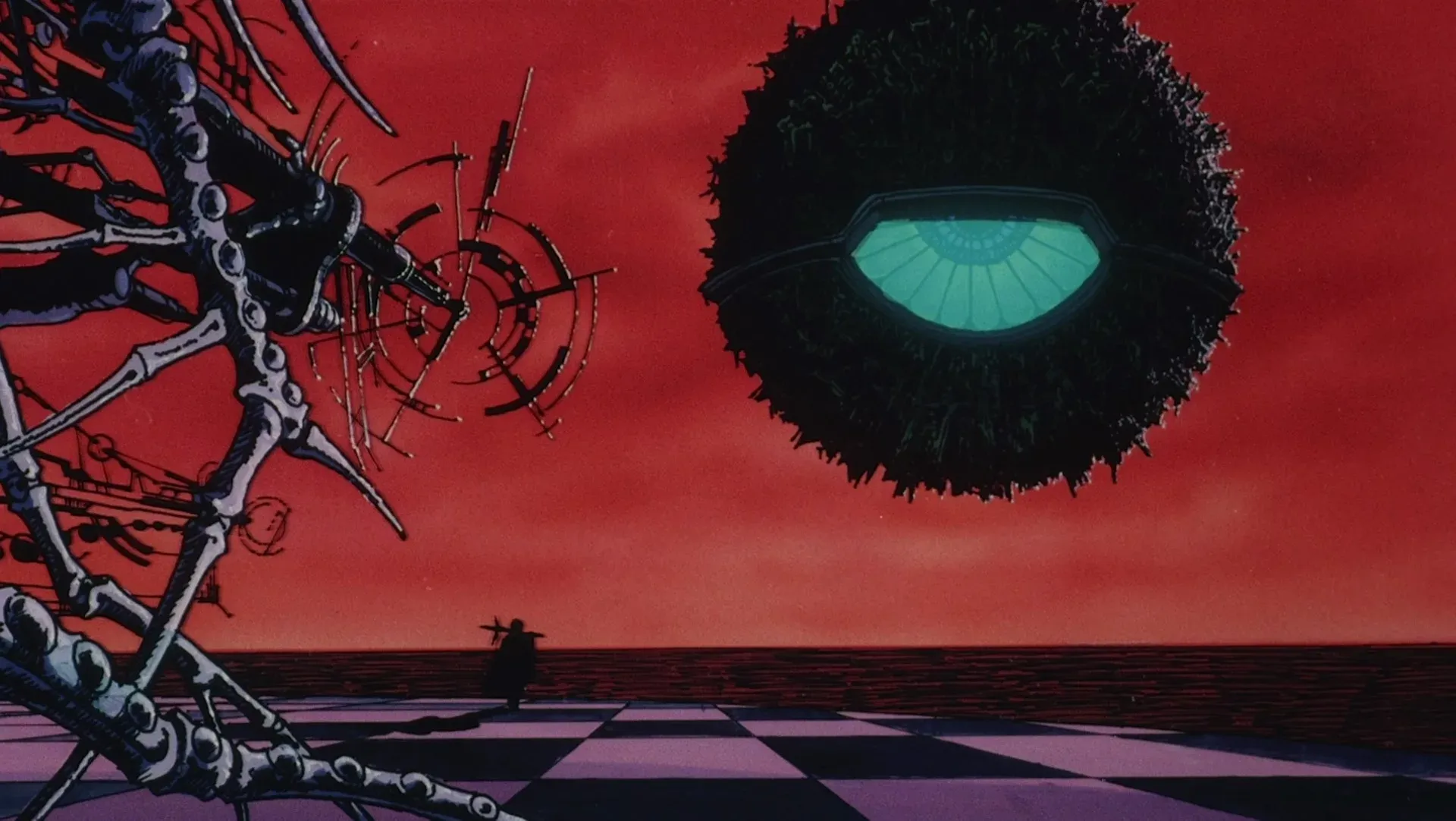

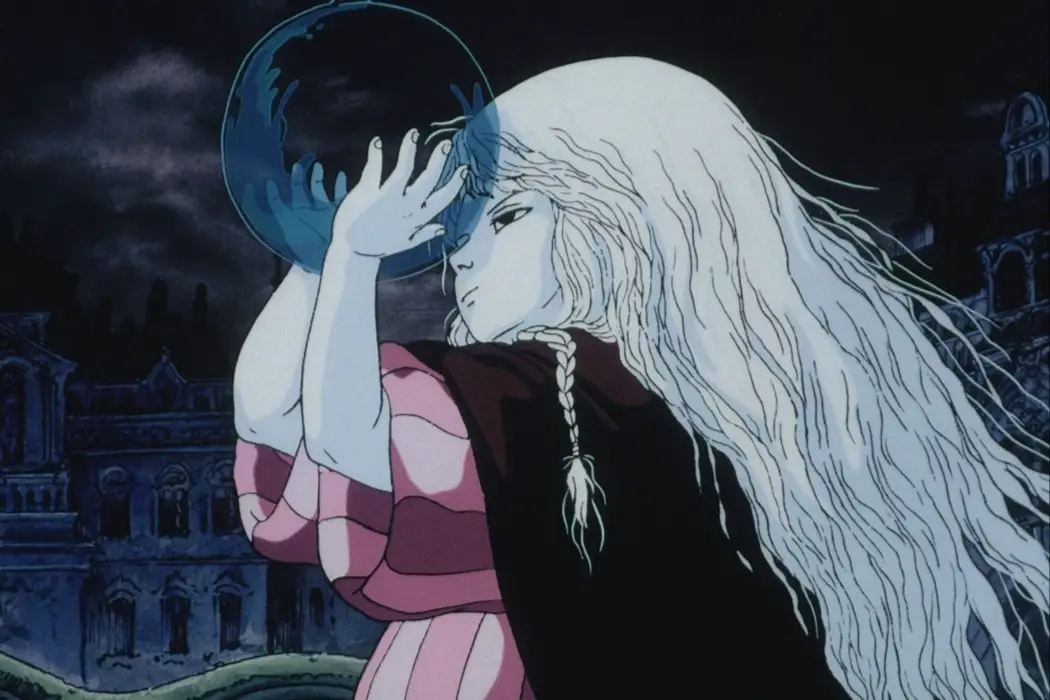

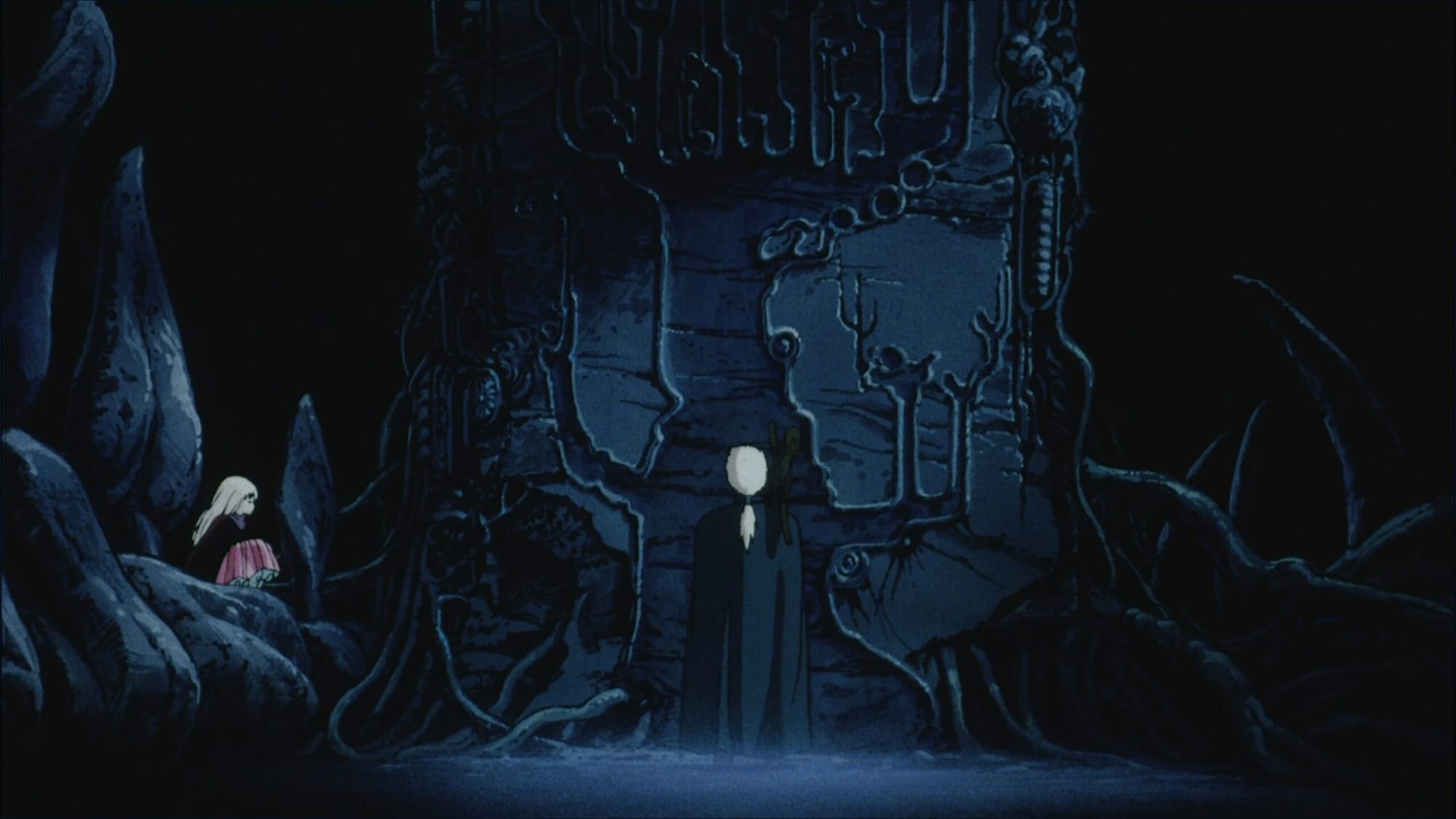

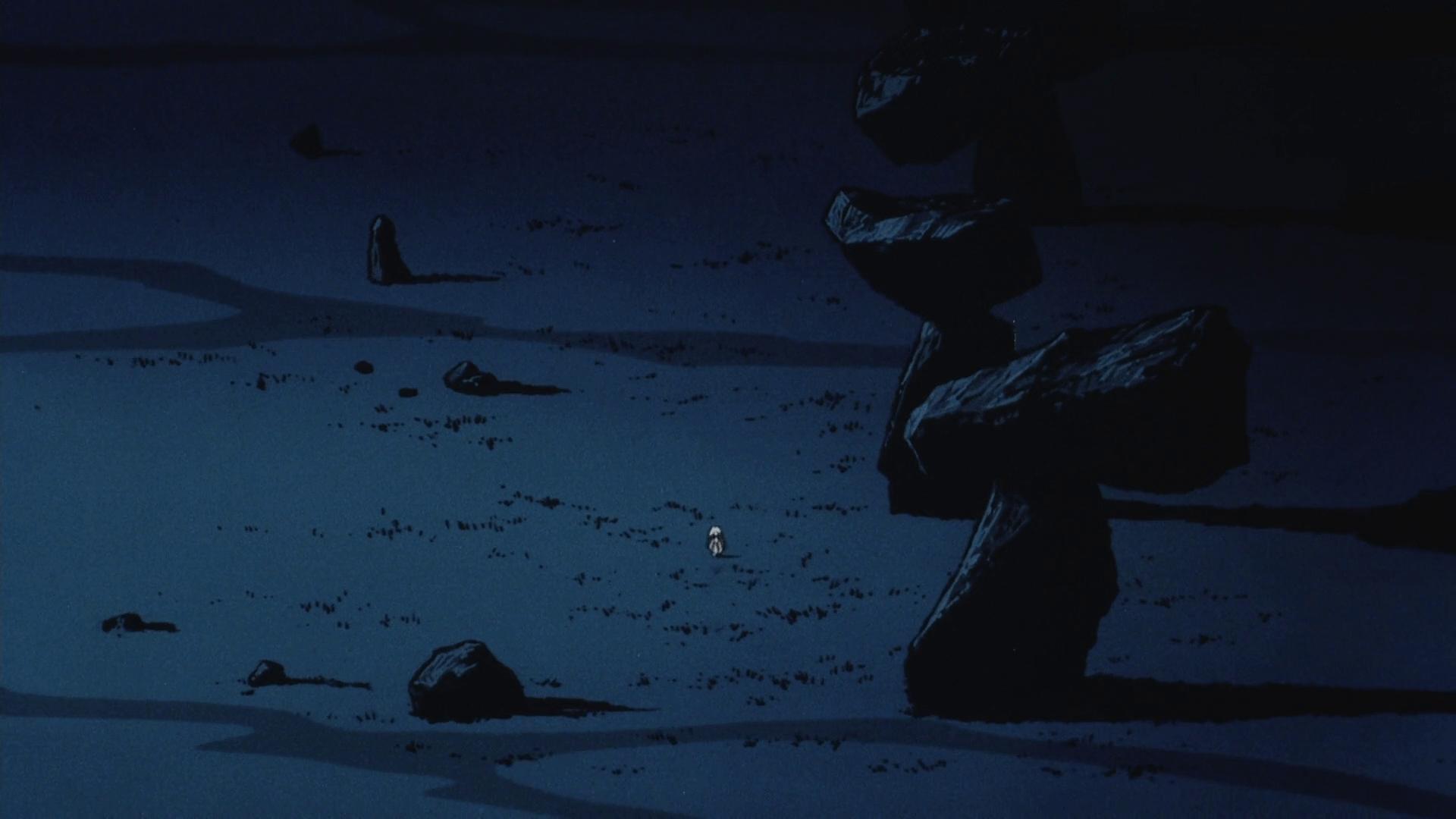

Angel’s Egg is a collaboration between Oshii and artist Amano Yoshitaka (Final Fantasy, Vampire Hunter D), with Oshii writing and directing and Amano doing the art direction. It begins with a young man who carries a large, cross-shaped weapon watching a strange spherical object descend from the sky. Later, we see a young girl get up and walk around, pick up a large egg, and begin carrying it to and through a desolate city. Their world is mostly deserted and quite damp. Occasionally, she'll see some other people, such as an army of identical men marching carrying fishing poles, attempting to capture the shadows of fish that float across the sky, visible only by the shadows they cast on buildings. Along her journey, she often stops for water, filling nearby glass jugs and looking through them. In the city, itself styled after a 19th century European town (tall gabled roofs, cobbled streets, central squares adorned with fountains), she meets the young man from the opening, who is riding along with a formation of mysterious red tanks. He joins her for her trek, despite her misgivings.

There’s very little in the way of dialogue in the story, and what words there are are mostly mysterious. At one point, the man recounts a version of the story of Noah’s Flood, which would seem the key to unlocking the mystery of What This Movie Is About. In the story, Noah releases a dove to learn if the Flood is over, but the dove never returns, and the people on the Ark eventually forget all about it, carrying on in the Flood forever, with no memory of the world before, and he suggests that the dove never existed. The girl insists that it did, and leads him to a tall building wherein they find a petrified skeleton of a humanoid creature with wings (an angel, you might say). She believes this was the dove, and that her egg is related to it. But while she’s sleeping, he smashes the egg, trying to prove her belief is illusory. Distraught, she falls into the now-flooded city, her final air bubbles birthing dozens of new eggs. This conclusion seems to mix in the story of Pandora’s Box, which ultimately contains, after all the evils of the world, hope.

Angel’s Egg was released straight to video (an OVA in anime parlance, the egg pun being wholly coincidental) and eventually became a cult classic both in Japan and abroad as its obscurity and openness to interpretation are highly prized among the obsessive and arty and its deliberate pace and lack of easy answers were (and remain) abhorrent to the mainstream. Like René Laloux’s Fantastic Planet, it’s an ideal midnight movie, its open spaces in plot and image ideal for floating within in the altered states of a late night audience. Seeing it today, it is most striking for its constructedness, the kind of slight scruffyness that comes from hand-drawn, multiplane animation that has been almost wholly lost in the decades since animation went digital. The film is remarkably static, with an unchanging background the image is given motion either by the movement of one of the two figures, often dwarfed by their surroundings, or simply by the movement of the camera alone. It truly is a world at its end, and by the dozens and hundreds of bottles we see along the girl’s path, it has been there for a very long time indeed.

We never know exactly how many times the girl in Angel’s Egg has made her journey, how many times she’s found her angel and lost her egg, or how many times she’ll do so in the future. This could be the first time, the last time, or merely one at random out of thousands. Time, the future, the past, have no really meaning in (the) film, the logic it follows is that of a dream, free associating across time and space, metaphorically at least if not always visually. The Red Spectacles, released two years later, is similarly governed by dream logic, but rather than a mysterious fable its story is a slapstick nightmare.

The opening image is familiar if you know the later anime written by Oshii and directed by Okiura Hiroyuki, Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade (or, if you’re like me, Kim Jeewoon’s 2018 live-action Korean remake Illang: The Wolf Brigade): a terrifying soldier in black armor holding a large gun, the only color on their body being a pair of frighteningly glowing red eyes. The soldier belongs to an elite unit of the police that has just been disbanded by government order for their use of excessive force. Three members of the unit have refused to surrender and are on the run. Resting in a warehouse, they are set upon and two of them are wounded. They offer to stay behind while the third escapes to a waiting helicopter. He vows to return eventually.

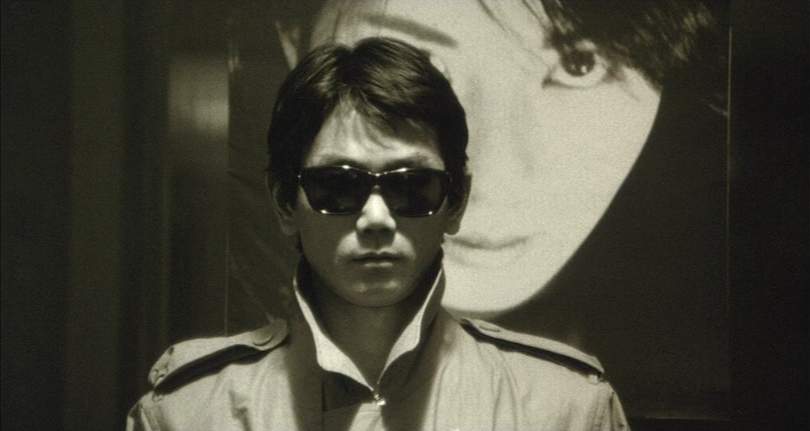

Three years later he does, and the film, in the beginning a recognizable full-color Japanese crime saga, complete with bullets and katanas, has turned black and white and entered Alphaville territory. The returning soldier, Koichi (Chiba Shigeru), wears dark sunglasses and a trench coat. On arriving in the city he feels like he’s being followed, and Oshii tracks him along the abstract architecture of a modern transit station at night, all sharp angles and shadows, footsteps resonating on the pavement. As he makes his escape, the film nods in the direction of silent comedy, and the film will oscillate between these two modes, modernist alienation and wacky hijinks, for the rest of its runtime.

This is the mode of early Godard, and while Alphaville is the strongest influence, especially visually, the way the film careens between absurdity and profundity recalls as well A Woman is a Woman, Le petit soldat, and Masculin-féminin among other classics. Koichi is in search of his former comrades, but nothing in the city makes sense to him anymore. His unit (the wolf brigade) are styled as dogs, while the enemy hunting him are cats: the hordes of bad guys he beats up make meowing sounds, and the city seems to be dominated by a corporation whose symbol is a cat’s face (their instant noodles taste terrible). One of his friends is now a pool hustler, whose introduction leads to a vaudeville-style musical number. One other, not one of the two he left behind but another former colleague, patronizes a noodle stand, one which is literally underground as the government has inexplicably banned noodle stands for being a baleful influence on society. Another plays the role of an orientalist kept woman (the hotel Koichi stays at is called The Orientalist) for a guy dressed like a North Korean dictator who seems to be in charge of the forces hunting Koichi. Her story alternates between tragic and heroic modes. Haunting him throughout his journey is a beautiful photograph of a woman, reproduced in hundreds of posters all over the city and playing on a loop in the movie theatre he finds himself waking up in more than once. In the end, she’ll become a living character herself, albeit one who only watches the action and somehow turns into Red Riding Hood(?).

If anything, The Red Spectacles makes even less sense than Angel’s Egg, though its potential interpretations are far less substantial, or at least less interesting to me on a mythological level. While it’s a wild ride, and certain sequences are deeply sad and others are goofily charming, it becomes a bit repetitive once you get used to its rhythms and ultimately its meaning boils down to something far more conventional than the earlier movie. It's a story about how times change and you can’t go home again. About how the modern world doesn’t make sense. About how everything is more boring and the food doesn’t taste as good as we remember. About how the state and corporations make everything worse. And especially how terrible it is to take guns away from murderous cops. At least, according to the cops that is.